How to Grow Lavender: Your Fail-Proof Guide to Fragrant, Flourishing Plants

Picture leaving on a sunny summer evening. Your very own lavender’s soothing, sweet scent permeates the air; its silvery foliage glows in the dark and its purple spires gently buzz with contentment from joyful bees. You could live this, not a dream from a garden magazine. A garden can be transformed by the appearance and aroma of a thriving lavender plant, therefore bringing a bit of the Mediterranean right to your door and a refuge for the pollinators that pass by.

TL;DR: Your Lavender Success Plan

- Start with the Right Plant: Your success is 90% determined before you dig. The most crucial step is choosing a lavender variety that matches your climate and goals.

- For Cold Climates (Zones 5-9): Choose English Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia). It’s the most cold-hardy and the best for cooking due to its sweet, floral scent.

- For Hot, Humid Climates (Zones 7-10): Choose Spanish Lavender (Lavandula stoechas). It loves heat, blooms early, and has distinctive “bunny ear” flowers. Its scent is more pine-like.

- For the Strongest Scent (for crafts): Choose Lavandin (Lavandula x intermedia). This large, robust hybrid produces a powerful camphor-heavy fragrance, perfect for sachets and bouquets, but not for eating.

- For Year-Round Blooms (in frost-free zones 8-10): Choose French Lavender (Lavandula dentata). It is identified by its toothed leaves and has a milder, rosemary-like scent.

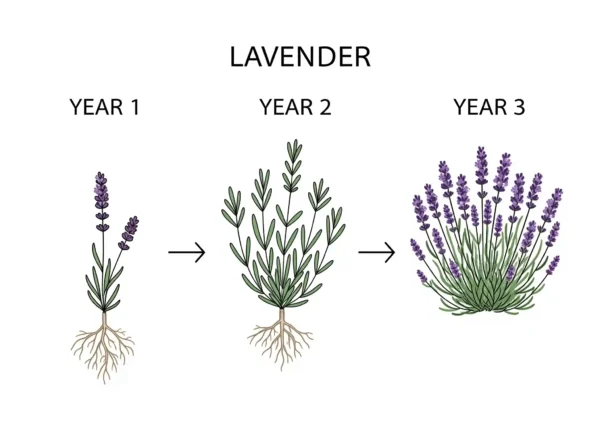

Every lovely lavender hedge, though, appears to have a tragic tale about a plant that, after just one season, turned into a gray, brittle twig. It’s gained a reputation for being picky, a diva in the yard that expects ideal conditions. If I informed you, though, that reputation is earned unfairly. If the secret to rich, aromatic lavender is just knowledge and observance of its three golden principles instead of any miraculous green thumb?

This is unique guidance. From selecting the ideal type for your particular climate to the pruning techniques that keep a plant healthy for decades, we will simplify the process entirely. This is about how to make lavender flourish rather than only about how to cultivate it; it will help you to become the confident gardener you were destined to be.

All set to create a fragrant, lovely reality from your lavender dream? Let us get our hands messy.

More Than Just Purple: A Handbook for Selecting the Ideal Lavender for Your Garden

Your path to lavender success starts far before of your digging of a trench. It begins with selecting a plant that really wants to live where you live. More than nearly any other, this choice will put you in position for success rather than disappointment. Let us meet the major lavender family players.

English Lavender: The Dependable Classic (Lavandula angustifolia)

Usually, those who dream of lavender are imagining this. Though its name may trick you; it is native to the Mediterranean, most gardeners throughout the United States choose it because of its remarkable cold hardness (thriving in USDA Zones 5-9). Unquestionably the monarch of culinary lavender, its scent is the gold standard: extremely sweet and flowery with very modest campher overtones. This is your plant if you want to create shortbread or lavender lemonade. Usually having a shorter stem and a narrower bloom spike than other types, it is ideal for tidy hedges and borders.

- Look for varieties like:

- ‘Hidcote’, with its deep purple blossoms and small form.

- ‘Munstead’, with its traditional scent and heat tolerance.

- ‘Royal Velvet’, with its rich, dark color and long stems ideal for cutting.

Spanish Lavender (Lavandula stoechas): The Ornamental Show-Off

When you see this one, you will recognize this one! The beautiful, petal-like bracts that instantly identify Spanish lavender from the top of the flower head—looking just like tiny bunny ears. A star for gardens in the South and California, this true sun-worshipper thrives in the heat and humidity English types would find difficult. Often beginning in spring, it blooms far earlier than other lavenders; be advised, though, it is best suited for warmer climes and is not frost-tolerant (Zones 7-10). Its fragrance is more pine-like and vegetal than sweet.

Lavandin (Lavandula x intermedia): The Fragrance Powerhouse

Look at the name; that small “x”. That indicates Lavandin is a hybrid, created especially for vigor and a remarkable oil yield by combining English and Portuguese lavender. These sturdy, big plants may create amazing mounds with long, graceful branches ideal for creating scented wands or big dry bouquets. Though significantly stronger in camphor, the aroma is strong and forceful and has a more therapeutic quality. Most commercial lavender oil applied in cleaning agents and soaps comes from this source.

- Popular variants are:

- ‘Grosso’ for its strong scent and dark blossoms.

- ‘Provence’ for its classic use in French crafts and great heat resistance.

French Lavender (Lavandula dentata): The Year-Round Bloomer

For those in really moderate, frost-free areas (Zones 8–10), a great but less well-known choice. The unusual leaves of French lavender, with their exquisite, toothed or serrated edges, acquire their name from. Its very long bloom period is its best quality; in the correct temperature, it can bloom almost year-round. More of a decorative beauty than a fragrant powerhouse, the scent is far gentler and more like rosemary.

| Variety Type | Best For | USDA Zone | Scent Profile | Mature Size |

| English Lavender | Cold climates, culinary use, classic sweet scent | 5 – 9 | Sweet, Floral | 2-3 ft. tall & wide |

| Spanish Lavender | Hot, humid climates, unique visual appeal | 7 – 10 | Herbaceous, Piney | 1-3 ft. tall & wide |

| Lavandin | Large hedges, crafts, high fragrance output | 5 – 9 | Strong, Camphorous | 3-4 ft. tall & wide |

| French Lavender | Mild, frost-free climates, long bloom season | 8 – 10 | Mild, Rosemary-like | 2-4 ft. tall & wide |

Your Guide for Lavender Planting (and Correcting First Time Errors)

Once you have selected your lavender champion, it is time to design its ideal habitat. Here we really get to address the core of things. Lavender is unyielding about its basic demands; it does not need pampering.

First Golden Rule: Honor the Sun

The first and most crucial directive on lavender care is this one. Your plant need minimum eight hours of direct, full sunlight every day. Everything is powered by sunlight; it drives the development, promotes a profusion of blossoms, and most crucially concentrates the plant’s essential oils, producing the sedative scent that everyone yearns for. A lavender’s paradise is an area roasted by afternoon sun.

Number Two Golden Rule: It’s Mostly About the Drainage.

If sun is the first commandment, this is the second, and perhaps the one that results in most failures. The first time I realised what “perfect drainage” actually meant for lavender will always be remembered. In my lush, healthy garden soil, I had laid a lovely row, and within a month they were yellow and dead. The teaching is Standing water will literally suffocate lavender roots, causing the dreaded root rot. You have to imitate the way they developed on the arid, rocky Mediterranean slopes.

- Useful Tip: The Percolation Test Not sure whether your soil drains? Consider this. Dig a hole roughly one foot wide and one foot deep. Load it with water, then let it totally empty. Fill it one more then timing the emptying process. Your drainage requires major assistance if it still holds water several hours later.

- The Perfect Soil: You want the perfect lavender soil to be either sandy, gravelly, or gritty. Not hopeless if you have heavy clay soil! Changing your soil will help you to design a flawless house. Mix one-third compost (for a small nutrient boost) and one-third inorganic material like coarse builder’s sand (not play sand) for every shovelful of clay you remove from the planting hole. These elements provide air pockets in the ground that let water to flow naturally. Plant your lavender on a naturally occurring slope or in a raised bed for a really fail-proof approach. Your friend going to be gravity.

- ProTip: Check the soil pH; lavender grows best in neutral to somewhat alkaline soil (a pH of 6.5 to 7.5). Most garden soils have a faint acidic quality. When you plant, add a tiny bit of lime or wood ash to “sweeten” an acidic soil. A basic soil test kit available from a garden retailer will get a clear reading and eliminate some of the guesswork.

To Mulch or Not to Mulch?

Many well-meaning gardeners fall at this crucial junctur. Lavender suffers death from conventional organic mulches including straw, bark, or wood chips. Their moisture retention quality is exactly the reverse of what lavender prefers. One-way ticket to decay is this trapped moisture at the base of the plant. Give your lavender a “stone mulch,” instead. The ideal finish is one-inch layer of crushed shells, light-colored pebbles, or pea gravel. It makes a plant feel perfectly at home by keeping the crown dry, controlling weeds, and reflecting heat back up to the plant.

Technique of Planting

- Dig a hole just as deep but double the width of the nursery pot.

- If necessary, use the procedure above to change the dirt you pulled from the hole.

- Carefully take the plant from its pot and gently tease any roots circling the bottom.

- Arrange the plant in the hole such that the top of its root ball—the crown—is around one inch above the level of the surrounding ground. This is a critical step to stop water from gathering at its base.

- Fill the hole with your changed dirt to produce a modest mound with a sloping away from the center of the plant.

- Once to settle the dirt around the roots, water thoroughly once. Then, back off. Water it just once; wait till the ground is entirely dry.

Space is essential.

Plant lavenders close together for a quick full look, but fight the impulse! In humid regions specifically, good air circulation is essential for preventing fungal illnesses. Plant kinds of English lavender minimum two to three feet apart. Though right now it may seem scant, in years to come you will be rewarded with better, more spectacular plants.

Never Get Afraid! Pruning lavender to prevent it from being woody

Welcome to the third and last golden guideline, the one separating a long-lived, content lavender from one that goes out in a few short years. Among the most crucial acts of care you can offer is pruning. Consider it as a structural haircut encouraging a strong, dense framework instead of allowing the plant to turn into a top-heavy, twisted mess.

Reasons for Pruning

The only thing keeping a lavender plant from growing a woody, brittle base is annual pruning. This aged wood at the bottom loses capacity for new growth over time. The woody base cannot support the growing and heavier leafy top and is likely to crack open under the weight of rain or snow, therefore destroying the plant.

Pruning’s Timing

There is great timing involved here. Right after the first significant bloom fade in mid-to-late summer is the ideal time to do the main structural pruning. This allows the plant time to produce some fresh foliage that will harden off before the first frost, therefore shielding it over winter. A very little shearing in early spring, just as fresh green shoots start to show, can be a secondary tip for shaping the plant and eliminating any dead stems from over winter.

Pruning Techniques:

Gardeners start to get anxious here, but I swear it’s easy. Go boldly! Cut the whole plant by at least one-third, then shape it into a neat, compact mound using up to half of that cut.

Here is the important, can’t-mess-it-up alert: Track the leafy stems down toward the plant’s base and make sure you always find a set of green leaves beneath where you intend to cut. Never, never cut straight, gray, aged wood from the base of the plant. Any cut made into such wood will be permanent and leave a dead area as that wood has lost its capacity to sprout fresh growth.

Regarding Deadheading

Deadheading is not like cutting back. It’s the easy habit of cutting off spent flower stalks all during the flowering season. Although not necessary for the long-term survival of the plant, frequent deadheading will help some varieties—especially English lavenders—to generate a second, smaller flush of flowers late in the season, therefore improving the beauty of the plant.

Gathering Lavender Like a Pro

Bringing lavender’s scent and beauty indoors is among the pleasures of growing it.

- Regarding drizzled bouquets: Harvest just the first one or two blossoms at the base of the spike; the flower buds have formed and colored up. At this point the buds are least likely to break off after drying and the color and aroma are most concentrated. Cut lengthy stems; collect them into little bundles using a rubber band; then, hang them upside down in a dark, warm, dry environment for several weeks.

- Culinary Use: Harvest the blossoms at the same stage—just as they start to open. These can be used fresh or dried for later use. Lay the flower stems one layer on a screen or a fresh cloth to dry. After completely dry, softly brush the buds from the stems.

- For fresh crafts like lavender wands, pick stems while the flowers are fully open for optimal flexibility, even though you can harvest at any point.

Level Up Your Lavender Game: Common Problems Solved & Pro Advice

Prepared to advance from apprentice to master? Allow me to address some advanced subjects.

Planting Lavender in Pots

A great approach to manage the soil and introduce lavender onto a deck or patio is growing in containers.

- Choice of Pot: Since terracotta is porous and lets the soil breathe and dry out fast, it is the greatest material available. Make sure the pot boasts lots of drainage holes. Lavender likes to be a little snug in its pot; pick a container only a few inches larger than the root ball of the plant.

- Perfect Soil Mix: Steer clear of the excessively water-heavy common potting mix. Combining one part excellent potting soil with one part perlite or coarse sand and one part small pebbles or grit will create your own ideal, sharp-draining mix. Another great pre-made cactus/succulent mix is this one.

- Lavender overwintering in pots: Container lavender suffers in colder areas (Zone 6 and below). After a few harsh frosts, let the plant become dormant; then, place the container in a covered, unheated area such as a garage, shed, cold frame. You want it to remain frigid, yet shield against strong winds and freeze-thaw cycles? Water it very sparingly—perhaps once a month—just enough to prevent total desiccating of the roots.

Guide on Troubleshooting

Why are the leaves of my lavender yellowing?

Nine times out of ten, this is either improper drainage, overwatering, or both root rot. The ground is very moist. Right away evaluate the circumstances. If it’s in a pot, let it totally dry out. If it is in the ground, your soil could not be draining sufficiently.

Why does my lavender not bloom?

The three offenders most likely are: 1. Not enough sun. 2. Too rich soil or too much fertilizer increases leaf development at the price of flowers. 3. Instead of waiting until after it bloomed in summer, you unintentionally clipped off the flower buds during a severe spring prune.

Why is the middle of my lavender plant split and floppy?

This is the classic sign of a plant neglected for several years without having been pruned correctly. The heavy top development cannot be supported by the woody base anymore. By now saving can be quite challenging, hence yearly pruning is really essential.

Encouraging lavender

Are free plants what you want? It is simple! Look for a robust, sturdy but not yet woody stem in late spring or early summer; this is known as a softwood cutting.

- From the stem tip, cut a 4-inch portion.

- Strip the leaves gently off the bottom two inches of the cutting.

- To aid stimulate root development, dip the bare end in rooting hormone powder.

- Plant the cutting in a shallow container loaded with sandy, moist soil.

- To make a mini-greenhouse, cover the pot with a clear plastic bag and position it in a brilliant spot out from direct sunlight. You should get a fresh, rooted lavender plant in few weeks!

Ultimately

You’ve made it! From selecting the proper type to the secrets of its long-term maintenance, we have traveled through the whole life of lavender. recall Lavender’s Three Commandments: 1. You Shalt Give Full Sun. 2. You are supposed to give perfect drainage. 3. You Should Prune Annually.

You have cracked the code by knowing and honoring these basic ideas. You have all the tools you will need for a lifetime of prosperity and have discovered the secrets separating struggling lavender from exquisite lavender. You know how to grow lavender; you no more have to question how.

Go forth now and design the lovely, aromatic garden of your fantasies!

Often Asked Questions

Is lavender something I could grow indoors?

Not advised for beginners and quite difficult. The main problem is light; lavender requires an amazing concentration of direct, strong sunshine that even a sunny windowsill can seldom supply. Should you wish to experiment, you will need strong additional grow lights going for much of the day and must exercise great caution not to overwater.

Lavender plants last what length of time?

The management of a lavender plant determines practically all aspect of its lifetime. Proper soil and yearly pruning help a well-kept English lavender to survive brilliantly for 15, 20, or even more years, growing more twisted and lovely with age. Neglected, unpruned plants could turn into an unattractive, woody jumble that falls apart in as little as three to five years.

Should one cultivate lavender from seed or plants?

Starting with known plants from a nursery is by far the simpler, fastest, and most dependable way for beginners to succeed. Usually needing a period of cold stratification to sprout, lavender seeds can be slow and famously difficult to germinate. Starting with a plant allows you to concentrate straight away on supplying appropriate growing circumstances.

Which are suitable lavender companion plants?

Imagine Mediterranean. Plants that share the same conditions—full sun, lean soil, and great drainage—are the best friends. Perfect friends are other drought-loving herbs such sage, thyme, and rosemary. Sun-loving perennials that like dry feet—like Echinacea (coneflower), Sedum (stonecrop), Gaura, and decorative grasses—also make great, low-maintenance friends that accentuate lavender’s texture and form.

Why did my lavender lose color and not return following winter?

In colder parts, this is a typical problem. Two most likely offenders exist here. First is root rot in damp, cold winter ground. Should the drainage be inadequate, the roots just rot away before spring. The second offender is a false spring, whereby a warm spell fools the plant into developing fragile new growth only to have that new growth killed by a later hard freeze. Your strongest defenses are good mulching with stone and guarantees of great drainage.