Why Your Lavender is Dying? The Climate Zone Secret to Success

Have you ever gone by every guideline? You have ideal soil, a full day of sunlight, and well-kept pruning; only to have your lovely lavender decay in a humid summer or expire in a rainy, cold winter. If this narrative seems familiar, you have found the most crucial secret of the gardener: the success of a plant depends on climate not only on maintenance.

TL;DR: The Lavender Climate Code

- USDA Zones Aren’t Enough: A plant tag’s zone number only tells you about winter cold. It doesn’t account for the two biggest factors for lavender success: summer humidity and winter wetness.

- The Ideal Climate: Lavender thrives in conditions that mimic its native Mediterranean habitat: hot, dry summers and mild, relatively dry winters.

- The #1 Climate Killer: Winter Wet. Cold, soggy soil will rot the roots of even the hardiest lavender. Excellent drainage is non-negotiable in wet climates.

- The Invisible Enemy: Summer Humidity. Sticky, damp air promotes fungal diseases. Good air circulation (wide spacing) is critical in humid regions.

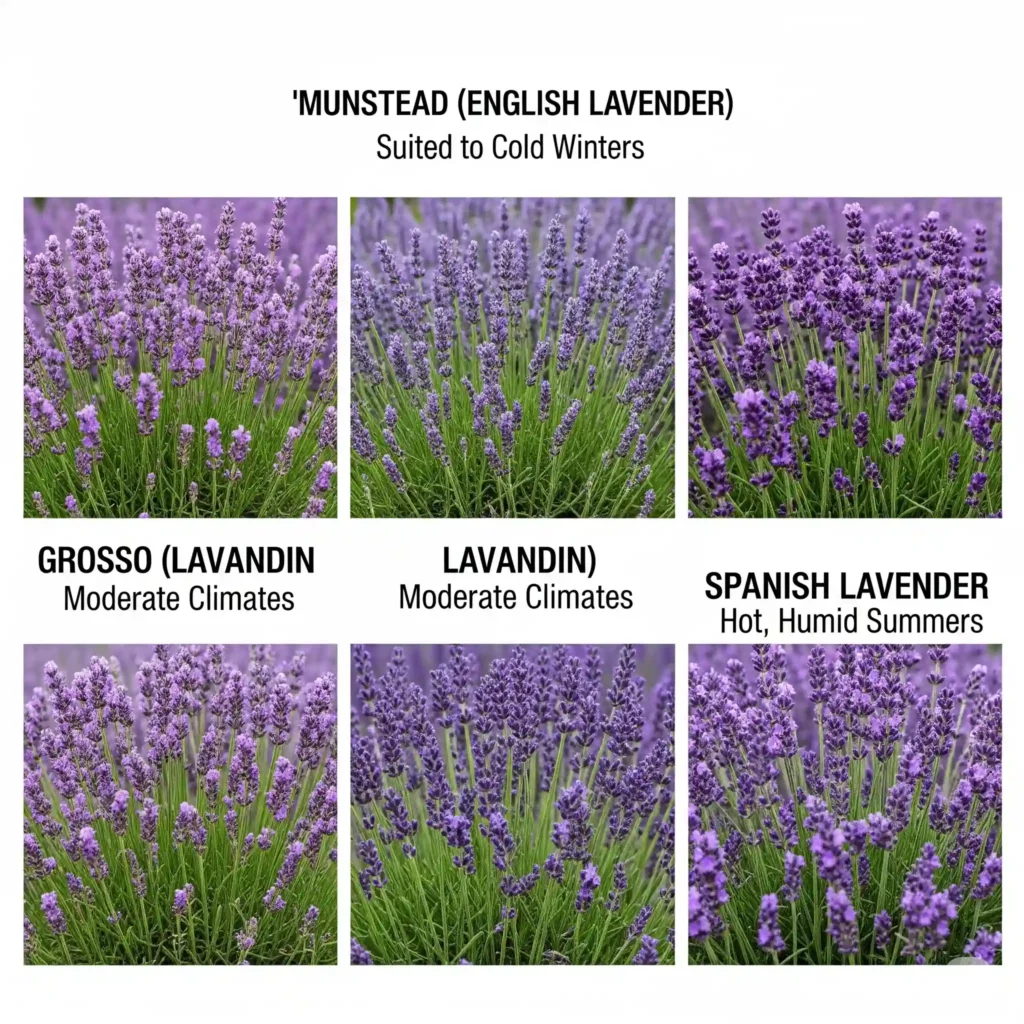

- Climate-Based Lavender Choices:

- Cold Winters (Zones 5-7): Your best bet is English Lavender (L. angustifolia). It’s the most cold-hardy.

- Hot, Dry Summers (Southwest, California): The perfect zone. Spanish, French, and English Lavenders all thrive.

- Hot, Humid Summers (Southeast, Midwest): This is the toughest challenge. Stick to heat-and-humidity-tolerant varieties like Spanish Lavender, French Lavender, and specific Lavandin hybrids like ‘Phenomenal’. Container growing is often the best strategy here.

- Wet Winters (Pacific Northwest, Northeast): Success depends entirely on drainage. Use English Lavender and plant it in raised beds, on slopes, or in containers.

What therefore is the ideal temperature for lavender? Let us straight forwardly get right on it. The perfect lavender climate zones are those that resemble its natural Mediterranean habitat: areas with hot, dry summers and quite warm, rather dry winters.

For most of us, the difficulty is that a basic USDA Hardiness Zone number on a plant tag only indicates how cold your winter gets; it says nothing about summer heat, rainfall, or that invisible enemy, humidity—the same conditions that so often define success or failure for lavender.

Still, don’t let discouragement set you back. This book will demystify these elements of climate. Consider it your own road map, guiding you throughout the nation’s varied weather patterns to select the ideal lavender that will not only survive but actually flourish in your particular area.

All set to find which lavenders would thrive in your yard? Let’s investigate the several climates found in the gardening universe.

Why Do USDA Zones Tell Only Half the Story?

Every gardener familiar with USDA Hardiness Zone. Telling us the typical annual low winter temperature for our region and instructing us on which perennials might withstand the cold, this is absolutely vital information. The secret is, though, that for a plant like lavender, it is only half the tale. With its dry air and strong sun, your Zone 6 in arid Denver is unlike a Zone 6 in humid Ohio with its summer thunderstorms and moist air.

Looking beyond the zone number at the “Big Three” climate parameters will help us to really grasp lavender’s requirements:

- Winter Cold & Wetness: Lavender’s killer number one is this combo. The damage is not from the cold itself but rather from roots buried in frozen, damp, or dry ground for months on end.

- Summer Heat & Sunlight: The motor of development, blossoms, and scent is summer heat and sunlight. To create their own essential oils, lavender yearns for heat and strong sunlight.

- Humidity & Air Circulation: The invisible foe is humidity. High humidity stops liquid from evaporating from the soil and foliage, thereby providing ideal habitat for the fungal infections lavender is so prone to.

One analogy I really enjoy is a USDA zone as understanding the lowest oven temperature setting. Still, the general temperature indicates whether you should be utilizing the “bake” (dry heat) or “steam” (wet heat). With lavender, you always want to bake—not steam.

Selecting the Appropriate Lavender for Your Area: A Climate-by-Climate Analysis

Let’s explore the United States and see how these climate variables interact to determine which lavenders would grow most suited in each area.

California and The Southwest (The Perfect Zone)

Lavender heaven is what this is. The mild winters and hot, dry summers exactly reflect the Mediterranean.

- Challenge: Even this sun-loving plant can occasionally be stressed by the strong, burning sun of the low desert areas of Arizona and Nevada.

- Advantage: Lavender is almost meant for this environment. Low humidity, lots of sunlight, and dry conditions abound here.

- Best Bets: You could nearly grow anything! Here are amazing heat-loving Spanish lavender and French lavender. Though in the extreme hottest inland places, Hardy English Lavenders also thrive wonderfully; they might value a little light shade during the sweltering late afternoon hours to prevent them from shutting down.

The Pacific Northwest (Mild, Dry Summers; Cool, Wet Winters)

With a major obstacle to overcome, this area can surprisingly be wonderful for lavender.

- The challenge is the fabled winter rain. Root rot is brought on by the combination of low temperatures and constantly moist fall through spring soil.

- Advantage: Summers are generally brilliantly sunny and dry, ideal for the flowering season of lavender.

- Best Bets: Cold-hardy plants. Here the champions are English lavender. But success is nearly totally predicated on offering outstanding drainage. Not only is planting on a natural slope, in a raised bed, or in a gravel rock garden a nice idea; it is absolutely vital.

Mountains West (Dry Air, Cold Winters, Strong Sun)

High elevations provide a special set of circumstances that can be the dream of a lavender-lover.

- Challenge: Plants may suffer greatly in extreme winter cold and severe temperature swings in spring.

- Advantage: The dry air causes humidity to be non-problem. The strong, high-altitude sun encourages amazing synthesis of essential oils, which produces some of the most aromatic lavender you will ever smell.

- Best Bets: Reliable selections are only the toughest, most cold-hardy English Lavender varieties, including “Munstead” and “Hidcote.” Here, a regular winter snow cover is rather helpful as a dry, fluffy insulation against strong cold winds.

The Midwest (hot, humid summers; cold, snowy winters)

In the heat, this area provides a big problem.

- Summer humidity presents a difficulty. The wet, sticky air of a Midwest summer is the enemy of lavender, encouraging fungal diseases on the leaves.

- One advantage of a consistent winter snow cover is its ability to effectively insulate against the cold.

- Best Bets: Stay with strong, cold-hardy English Lavenders and vigorous Lavandin hybrids. Here success depends on perfect air circulation. This implies using a gravel mulch instead of wood mulch to keep the base of the plant dry and broad distances between plants—3–4 feet are not too much.

The Northeast (moderate, humid summers; cold, wet winters)

This can be a difficult area combining the difficulties of cold and humidity.

- Challenge: Moderate summer humidity combined with “winter wet” (cold rain and snow on partially frozen or unfrozen ground).

- Advantage: Some cultivars may find less stress if summer heat is usually less strong than in other areas.

- Best Bets: Ground efforts should focus on only the toughest English lavenders. A classic pick for a reason is “Munstead”. Here, raised beds or container gardening are strongly advised since they allow you total control over drainage.

The Toughest Challenge, the Southeast and Gulf Coast

Unquestionably, this is the toughest area of the nation for cultivating traditional lavender.

- Challenge: year-round heavy rains and extreme, relentless summer humidity. The natural habitat of lavender is the antithesis of these conditions.

- Advantage: Winter cold never presents a problem.

- Best Bets: Most English Lavenders will just melt; they are not really relevant. Your only actual candidates are specialist variants developed for resistance to heat and humidity. Search for heat-loving Spanish and French lavenders as well as certain particular Lavandin varieties like the aptly titled ‘Phenomenal’. Since container growing permits complete control over soil moisture, most gardeners in this area find it to be the only surefire way to succeed.

Your Lavender, Your Climate: a Variety Cheat Sheet

Let us simplify that area tour into a basic buyer’s manual.

- For Zones 5–7, Cold Winters & Wet Conditions: The English Lavenders (Lavandula angustifolia) are the clear champs. Their hardy nature stems from their higher altitude European background. Search for time-tested variances such “Munstead” and “Hidcote.”

- The main players for Extreme Heat & Humidity (Zones 8–10) are French Lavender (L. dentata) and Spanish Lavender (L. stoechas). Their particular genetic composition and leaf forms help them to be more suited for these demanding surroundings. Search also for strong Lavandin hybrids like “Phenomenal” and “Provence.”

- Often a wonderful middle-ground alternative are the Lavandin hybrids (L. x intermedia), which fit moderate climates. From their English parent, they usually have strong cold hardiness and from their other parent, better heat tolerance; so, they are active and dependable growers in various sections of the country.

Learn to be a Climate Hacker: How to Design the Perfect Lavender Oasis

Are you a committed gardener that enjoys challenges? Making microclimates in your own yard will let you break the rules. Like the famously heated spot against a south-facing brick wall or a windy corner that keeps dry, a microclimate is just a tiny area where the conditions differ somewhat from the surrounding area.

Golden Knuckles: Professional Secrets for Expanding Boundaries

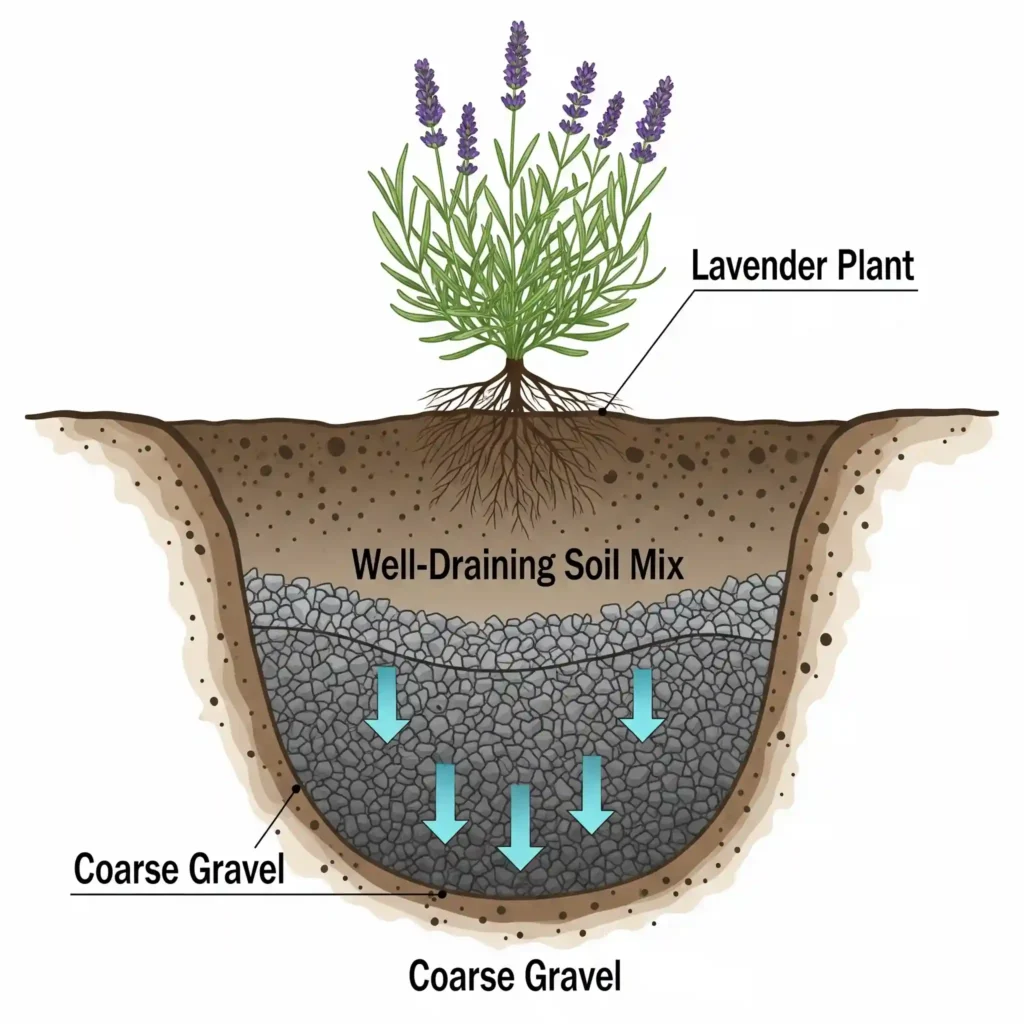

- The “Gravel Sump” for Humid Areas: For Southeast and wet Midwest gardeners, this is my number one secret. Dig your planting hole four to six inches deeper than the root ball calls for. Before placing your modified soil on top, fill this bottom layer alone with coarse gravel. This produces a reservoir where extra water may safely gather away from the plant, a little French drain straight under the roots. It nearly makes rot impossible, even in the wettest of conditions.

- Diagnosing Your Winter: You have to recognize your enemy—desiccation vs drowning.

- Does it seem to be “Winter Wet”? (Northeast, PNW, weter Midwest): Here the killer is roots buried in mushy, chilly ground. Elevation is the only one fix available. One cannot negotiate whether one plants on a raised bed or on a berm.

- Is “Winter Desiccation” the correct term? (Mountain West, with its breezy plains): Here the killer is dry winter wind taking moisture from the evergreen leaves while the roots are frozen and incapable of rehydrating the plant. Protection provides the answer. Using some pine boughs buried in the ground, build a basic windbreak on the plant’s prevailing windward side. Never wrap the plant in burlap since that can encourage decay by trapping moisture.

- The “Lean and Mean” First Year: This approach teaches resilience. In the first year of your lavender, be especially frugal with compost and water. As the plant hunts for resources, a small amount of difficulty drives it to create a strong, deep, broad root system. Unlike a coddled plant with a shallow, lethargic root system, this severe love produces a strong plant able to survive decades of drought and extreme circumstances.

- For a longer season (Zones 7+) the “Two-Step Pruning” is Try this to induce a second, striking bloom from your plant. First, taking the stems deep into the leaves, pluck roughly one-third of the flowers right at their absolute peak for cutting. Give the whole plant its primary structural shearing one week or two later when the last blossoms fade. Early harvest combined with a timely shear sometimes shocks the plant into producing a second, complete flush of fall blossoms.

In summary,

Success with lavender is about matching rather than about discovering a mystical, one-size-fits-all plant. It’s about honestly evaluating your local climate—its rain, humidity, heat, winter character—and selecting a lavender variety that finds those conditions pleasant. You are now qualified to see beyond a basic zone number and make a wise decision that will result in years of aromatic success.

Knowing the subtleties of lavender climate zones will help you to choose a plant for your garden that is not only surviving but really flourishing.

Often asked questions

I live in Zone 7, an extremely humid one. What is my ground-based absolute best chance for success?

Your best chance is a strong Lavandin hybrid like “Phenomenal,” which is noted for heat and humidity tolerance. To ensure drainage, you MUST, however, use a gravel mulch, give it broad spacing (at least 3-4 feet apart), and give much thought to adopting the “Gravel Sump” approach at planting time.

Is English lavender something I could grow in Florida?

Not advised and somewhat difficult is it. English lavender is virtually always killed by the combination of heavy summer heat, humidity, and rain. Treating a humidity-tolerant Spanish or French Lavender as an annual or short-lived perennial in a container would have far better success.

Does lavender benefit or suffer from snow cover in winter?

It depends on the main winter hazard your climate presents. A fluffy snow cover a great insulator against “winter desiccation” in cold, dry climes. In cold, rainy areas, a heavy, wet snow on poorly drained soil causes “winter wet” and root rot.

Like 7b/8a, my zone borders on the edge. Which kind ought I to go for?

Often a great choice in a transitional zone is a strong Lavandin hybrid (L. x intermedia). Offering the best of both worlds, it provides stronger cold hardness than a Spanish variety but higher heat tolerance than a standard English Lavender.