A Guide to Selecting the Right Blueberry Bush

Imagine entering your backyard on a sunny July morning, fingertips stained purple, putting luscious, sun-warmed berries straight into your dish of cereal. Surely it is the dream of the gardener. A perfectly fresh blueberry, overflowing with taste, is a prize unlike anything else.

For many gardeners, though, the reality is a depressing-looking bush that simply sits there. The leaves go crimson, hardly grow, and the few berries it generates are small and sour. One of the great heartbreaks in gardening, it makes one question, “What am I doing wrong?”

I am here to tell you it most likely is not your fault. The single most crucial element in producing abundant berries is selecting blueberry plants appropriate for your environment. Success is about knowing the demands of the plant as an integrated system of biology, soil science, and climate, not about having a magical “green thumb”. Your best manual for learning that system will be this one, preparing you for success before you ever start shoveling.

Unlocking the Most Important Secret of Your Climate: The Chill Hour Code

First we have to start with the most important, non-negotiable idea in the world of blueberries before we discuss varietals or soil. Chill hours. The first and most crucial step on your path is knowledge of this.

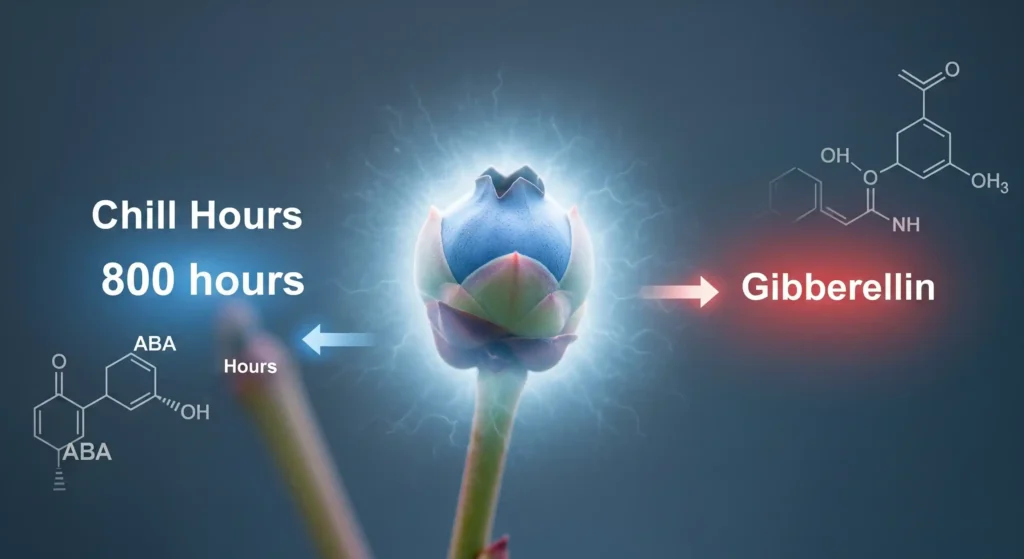

Consequently, what are they? In the winter, “chill hours” are the total number of hours a plant spends in conditions between 32°F and 45°F (0°C and 7°C). Consider it the necessary period of dormancy for a plant, a biological reset button. From a scientific standpoint, these hours of cold are required to break down a growth-inhibiting hormone called abscisic acid (ABA), which accumulates in the plant buds over the summer and fall. ABA levels remain high without a suitable cold spell, therefore blocking the springtime takeover of growth-promoting hormones (gibberellins). The outcome is a plant that does not leaf out, bloom, or grow actively.

One might consider it as charging a battery in great similarity. One designed for cold climates, a high-chill plant boasts a large battery that requires a lengthy, cold winter to fully charge. Designed for warmer climates, a low-chill plant charges its battery relatively rapidly.

This is the mismatch point.

- If you grow a Northern variety of a high-chill plant in Georgia, it never gets enough cold to completely charge its battery and breakdown the ABA. It wakes up in the spring feeling weak, disoriented, and devoid of the hormonal cue to generate blossoms.

- Low-Chill Plant in a Cold Climate: If you plant a Southern variety in Michigan, its little battery charges too quickly. It believes spring has arrived during a warm period in January and begins to bloom out only for those delicate young buds to be killed by the following unavoidable harsh frost.

Finding your local relax hours is simple advice for action. Often the agricultural website of a state institution is your greatest source. To locate interactive maps and data from local weather stations, try looking for [Your State] agricultural extension office or [Your State] chill hour calculator. Remember that cold hours may vary even on your own land; a low-lying, sheltered “frost pocket” will gather more chill hours than a windswept, exposed hilltop.

Introducing the Blueberry Family: Appropriate for Your Zone Matching a Variety

You can start to be a blueberry matchmaker after you know your expected chill hours. Meeting the family is time. Every branch has own personality, DNA, and perfect habitat.

Northern Highbush, Vaccinium corymbosum

- Calmer There are 800–1,000+ hours here.

- Best For (USDA Zones): 4-7 (the traditional option for the Northeast, Midwest, and Pacific Northwest)

- Derived from the wild highbush blueberry native to eastern North America, they are the big, straight plants that support the commercial blueberry business most especially. In areas having cold, snowy winters, they are dependable and quite efficient. Many times, variances are based on harvest time, which lets you budget for a supply spanning summer.

- Perfect for fresh eating, muffins, and pancakes, flavor and use value their classic, balanced sweet-tart taste and firm texture.

- Popular variances: Early-season: “Duke”; mid-season: ” blueray”; late-season: “Elliott”.

Southern Highbush, Complex Hybrids

- 150–600 hours for Chill Hours

- Best For (USDA Zones): 7–10 (the game-changer for Florida, the Deep South, and California)

- These are modern marvels; complex hybrids often comprising up to four different Vaccinium species. Plants that flourish in moderate winters and hot summers have been produced by breeders combining the heat tolerance of native Southern species with the great fruit size of the Northern Highbush. In warmer climes, they are often semi-evergreen.

- Usually quite sweet and delicious, flavor/use is great for all-around consumption.

- Popular varieties are “O’ Neal,” “Misty,” “Sharpblue.”

Vaccinium ashei, or Rabbiteye

- Chill Hours: 300 to 650 hours

- Best For (USDA Zones): 7-9 (the most tough option for the hot, humid Southeast)

- These are hard, robust plants named after the berry’s calyx, the little crown-like structure, which before ripening resembles a rabbit’s eye. More than any other type, they are robust to heat and drought and forgiving of less than ideal soil conditions. They are not, crucially, self-fertile. To get fruit, you have to plant at least two different Rabbiteye kinds close by one another.

- Often praised for their somewhat sweet taste and somewhat thicker skin, which helps them to freeze and maintain their shape in pies.

- Popular varieties are “Premier,” “Climax,” “Tifblue.”

Lowbush, sometimes known as Vaccinium angustifolium

- Chill Hours: 1,000 to 1,200 plus hours

- Best for (USDA Zones): 3–6 (the champion of the colder areas)

- These low-growing, spreading ground covers spread by underground roots known as rhizomes, not upright bushes. For an edible “living mulch,” this makes them quite a good choice. They generate the little, very delicious “wild” blueberries of trade.

- Prized for their strong, sophisticated, “wild” blueberry taste that accentuates sauces, pies, and jams.

Half-High: Hybrids

- Chill Hours: 800 to 1,000 plus hours

- Best For (USDA Zones): 3-7 (The flexible container champion)

- These hybrids, which combine a Northern Highbush with a Lowbush, present the best of both worlds: good fruit size and yield from the highbush parent and great cold-hardiness and compact height of the lowbush parent. When growing blueberries in big pots, they are the #1 choice.

- Taste/Usage: Superior, well-balanced taste on a plant not likely to overrun its available space.

- Popular varieties are “Northland,” “Chippewa,” “Polaris.”

Perfecting Blueberry Soil Preparation: The Acid Test

Getting the soil right comes somewhat closely second, even although selecting the correct variety is the most crucial stage. This is another non-negotiable and where many well-meaning gardeners fall short.

The “Why” for blueberries is that their pH falls between 4.5 and 5.5 and they must have acidic soil. There is chemistry involved here. Iron exists in higher pH (alkaline soil), but in an insoluble form (ferric iron, Fe³⁺) the plant cannot absorb. Blueberries’ need for acidic environments transforms this into the soluble, plant-available form (ferrous iron, Fe²⁺). Without this conversion, the plant is basically starved regardless of how much you fertilize it and suffers from iron chlorosis, the distinctive yellow leaves with green veins.

How should one test?

Not guess! A basic soil test kit from any garden center will provide you an accurate reading; for a more thorough investigation, submit a soil sample to your local county extension office. For a great possible return, this is a little outlay.

How to amend (detailed)?

- For Garden Beds: Elemental sulfur is the greatest long-term fix. Thoroughly mix about two pounds of sulfur into the top six inches of soil to reduce the pH of a 10x 10 foot area by one full point—that is, from 6.5 to 5.5. This is a lengthy, biological process; so, it would be best to do it in the fall, months before planting, as soil microorganisms have to translate the sulfur to sulfuric acid.

- When you plant a single bush, excavate a hole at least twice the width of the pot. Mix the excavated soil 50/50 with naturally acidic sphagnum peat moss to help retain moisture.

- The simplest approach to manage the soil is via container planting. Use a premium potting mix intended especially for acid-loving plants like rhododendrons and azaleas.

- Watch out for aluminum sulfate. Although it rapidly acidifies soil, over time aluminum poisoning can result. Long-term health calls for sticking to elemental sulfur.

Finding the Ideal Partner

Your soil is ready and you have your diversity. Let’s now discuss maximizing the berries one can acquire. Always grow at least two different types, here’s a basic guideline:

The “Why” is that, although many Highbush blueberries are technically “self-fertile,” this can be deceptive. The unusual bell form of blueberry blossoms calls for “buzz pollination,” a function most effectively supplied by bumblebees. Often more vigorous and compatible, pollen from a genetically diverse variety results in a far higher rate of successful fertilization. Better seed set follows from this, and this tells the plant to devote more resources—sugars, water—to that berry. The result is more bigger and more precisely formed berries, not only more berries.

Recall the Rabbiteye Exception: Cross-pollination is required for Rabbiteye varieties; it is not elective. Without a different Rabbiteye kind grown close by, they will generate almost none.

Look for varieties with a comparable bloom time (e.g., two “mid-season” types) when shopping for plants from a nursery. To maximize cross-pollination, plant them in a mixed block instead than in individual rows so that bees may wander freely between the several varieties.

Planting and First-Year Maintenance

Now comes the fun part! Getting your fresh plants in the ground and preparing them for a long, fruitful existence.

Planting Procedures:

- Choose a spot where at least six to eight hours of direct sunlight fall daily.

- Dig two times the width of the root ball but not much deeper. Fine, shallow root systems of blueberries expand outward.

- Take great care pulling the plant from its pot. If the roots are tightly coiled—that is, bound—be forceful. Either use a knife to make a few vertical slices down the side of the root ball or your fingers to pry them apart. This is absolutely vital to stop the plant from strangling itself.

- Make sure the top of the root ball is just above the surrounding soil level so the plant will settle somewhat.

- Using your changed acidic soil, gently tamping it down backfill.

- To settle the dirt around the roots, thoroughly and deeply water.

- Mulch in a 2–3 inch layer. Excellent options are acidic mulches including oak leaves, pine bark, or pine needles. Retaining moisture, controlling weeds, and adding to soil acidity as it breaks down mulch is absolutely vital.

Now for some tough love—the most important first-year advice. You have to pinch off any blooms that develop for the first year following planting. I know this feels wrong. It hurts to cut possible fruit. Still, it’s really vital. See it as distribution of resources. From photosynthesis, a young plant generates a limited supply of energy. You can concentrate that energy toward creating a few berries for one season or toward constructing a large root system “factory” to drive amazing output for decades to come. For a great long-term benefit, it’s a modest cost.

Finally, your blueprint for Blueberry Bliss

Blueberry success comes from knowledge and preparation rather than from luck or hope. The trip starts long before you even handle a shovel. It begins with knowing your particular environment, works through creating the rich, acidic soil blueberries need, and ends with wise planting techniques that will position your bushes for lifetime production.

You did the study. Look for your relaxed hours first. Second, pick from the corresponding blueberry family a variety. Third, promise acidic ground. Following these guidelines will have you done ninety percent of the work.

Right now, you own the most important puzzle parts. Selecting appropriate blueberry plants for your environment will drastically change the odds in your favor and enable years of sweet, locally grown harvests. Happy tending to your garden.

Often asked questions include

Imagine living on the edge of a zone, say Zone 7.

This is a really interesting inquiry. Often in a “transition” zone like 7, you have the most choices. Many Southern Highbush kinds, several late-season Northern Highbush varieties, and most Rabbiteye cultivars will help you succeed. To find out what grows best for other gardeners in your nearby area, your local nursery or county extension office is the best bet.

A new blueberry plant takes what length of time to start producing fruit?

Your second year might yield a meager handful of berries, but beginning in the third or fourth year you should expect a significant harvest. To help the plant to build a robust root system for more future harvests, remember to pinch off all the blossoms in the first year.

Could I grow blueberries in a pot?

Yes! This is a great choice particularly if your garden soil isn’t naturally acidic. Select a big container (at least 15 to 20 gallons) then apply a premium potting mix meant for acid-loving plants. Their more small scale makes half-high types like “Northland” or “Chippewa ideal for containers.

Why are the leaves on my newly acquired blueberry plant going either red or yellow?

Almost always, this indicates that the pH of the soil is too high—not acidic enough. The blueberry plant cannot absorb iron from the soil when the pH is off, which results in iron chlorosis—a nutritional shortfall. Either a fertilizer designed especially for acid-loving plants or a soil acidifier including elemental sulfur will help to reduce the soil pH.

For my blueberries, what kind of fertilizer ought I to use?

Apply a fertilizer designed especially for blueberries, azaleas, and rhododendrons—acid-loving plants. The secret is to hunt for one that supplies ammonium sulfate-based nitrogen. Nitrates can be poisonous to blueberry plants, hence avoid general-purpose fertilizers including nitrogen in nitrate form (such as ammonium nitrate or calcium nitrate). In the spring, use fertilizer sparingly when fresh development starts to show.