Yellow Leaves, Green Veins: Is Your Tomato Starving?

Understanding the Distress Signals of Your Tomato

Haven’t you? Those tomato plants have been nurtured by you with all your heart and soul. Images of a summer overflowing with ripe, red fruit twirl in your mind. Then you see it: those formerly rich, vibrant green leaves are beginning to fade to a concerning yellow. But the interesting thing is the veins. They are tenaciously clinging onto their green. What on earth is your tomato trying to say to you?

Stay calm! Many gardeners see this often. This post will explore in depth the causes of your tomato leaves’ classic “yellow leaves, green veins” pattern. Often known as interveinal chlorosis, this tell-tale symptom is typically a cry for help from a starving plant. We’ll look at the most typical nutrient offenders—consider them the necessary goods on your tomato’s shopping list. More significantly, we’ll work together as detectives to identify the precise deficit and, more importantly, how to properly nourish your starving tomatoes to restore their magnificent green.

Why does it all count? Understanding these visual signals from your plants, therefore, allows you to offer faster solutions. Healthier, more robust tomato plants follow from this, and finally, it puts you on the road to that rich, tasty harvest you are dreaming of!

“Yellow Leaves with Green Veins” is really what? Grasping Interveinal Chlorosis

So, what gives with this “yellow leaves with green veins” phenomenon? Though it may seem a little technical, the phrase interveinal chlorosis is really rather descriptive. Interveinal is just the tissue between the leaf veins. The yellowing caused by a lack of chlorophyll—the green pigment in plants—defines “chlorosis”. Interveinal chlorosis is therefore the condition in which the spaces between leaf veins become yellow while the veins themselves stay green. Think of it as a little roadmap where the roads (veins) remain obviously visible but the surrounding terrain (leaf tissue) is fading.

Why then is chlorophyll so crucial? From school biology, you may recall that chlorophyll rules when it relates to plant health. Through photosynthesis, it is the essential green material that lets plants create their own food by catching sunlight. Less chlorophyll indicates a struggling, undernourished plant unable to generate the energy required for survival and, more significantly for us, to bear fruit.

The encouraging news? This isn’t some uncommon, exotic illness that’s struck your cherished tomatoes. A visual indication that your plant is lacking one or more of its fundamental nutritional building blocks, interveinal chlorosis is rather frequent. Your tomato is basically saying, “Hey, I’m lacking something crucial down here!”

The Usual Suspects: Major Nutrient Deficiencies Causing Yellow Leaves & Green Veins

“Okay,” you might say, “my tomato is sending out an S.O.S. But which nutrient is it really wanting?” It’s like being a doctor, trying to diagnose a patient based on symptoms. Let’s get to know the main suspects usually in charge of this specific leafy complaint.

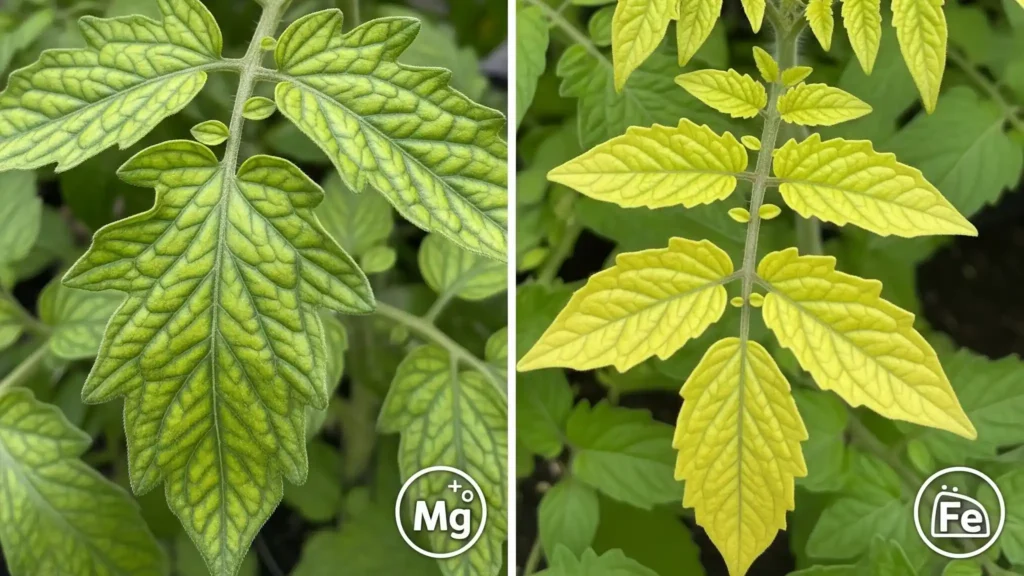

Magnesium Deficiency: The Chlorophyll Powerhouse

Magnesium comes first. Since magnesium is a key component of the chlorophyll molecule itself, consider it as a VIP in the realm of chlorophyll. Without magnesium, no vivid green. Magnesium doesn’t end there; it also significantly activates enzymes essential for good plant growth and fruit development.

How then can one identify a lack of magnesium?

- Usually, it begins with the older, lower leaves first. What for? Magnesium is a “mobile” nutrient, hence This indicates the plant is rather clever; if it is low on magnesium, it will scavenge it from the older, less vital leaves and send it to the new, actively developing areas like young leaves and fruit. If the deficit is not handled, you will usually notice the yellowing start at the base of the plant and progressively move up.

- You will notice the traditional interveinal chlorosis pattern: The spaces between the veins become yellow, occasionally with a mottled or marbled look. At least initially, the veins will stay clearly green.

- At times, the leaf edges could curl up.

- Particularly on the undersides, you could even see a reddish-purple tint on the leaves in more serious situations or if cool weather is a consideration.

What makes a plant low on magnesium? Many elements could be involved:

- Sandy soils are infamous for magnesium deficit since magnesium, being very soluble, leaches out quickly with rain or irrigation.

- High potassium levels in your soil may really hinder the plant’s capacity to absorb magnesium even if the soil contains magnesium. It’s somewhat like a race at the root level.

- Low pH acidic soils can also reduce magnesium availability for your plants.

- Heavy rain can wash away root zone accessible magnesium.

Iron (Fe) Deficiency: The Young Leaf Expert

Our following suspect is iron. Chlorophyll synthesis absolutely depends on iron; that’s the real process of producing chlorophyll. Many enzyme activities driving plant metabolism also much depend on it. Lack of sufficient iron prevents your tomatoes from generating the green pigment required.

The telltale symptoms of an iron deficit differ somewhat from magnesium:

- Usually, it first affects the younger, upper leaves. Unlike magnesium, plants consider iron to be a “immobile” nutrient. Once the plant adds iron into a leaf, it essentially remains there. Therefore, when the iron supply is low, the new growth—the fresh, young leaves at the top of the plant and on the ends of branches—will show symptoms first since the plant cannot transfer iron from older leaves to support them.

- Often, the pattern is a very sharp and striking contrast between bright yellow or even pale yellow leaf tissue and clearly dark green veins. Its appearance can be rather spectacular.

- Severe iron deficiency can cause the impacted leaves to become nearly creamy white and the general plant growth to be quite stunted.

What could be causing your tomatoes to lack sufficient iron?

- The main offender is high soil pH (alkaline soils). This is significant! Though the pH is too high—usually above 7.0 or 7.5—tomatoes cannot really absorb it. The iron is rendered chemically unavailable to the roots of the plant.

- Waterlogged or badly drained soils can also lower iron availability as the lack of oxygen alters the chemical form of iron.

- Occasionally, excessive amounts of other nutrients in the soil, such as phosphorus, manganese, or zinc, might hinder iron absorption.

Nitrogen (N) Deficiency: The General Growth Driver (A Supporting Role Here)

For plants, nitrogen is the workhorse mineral. Being a key component of chlorophyll (yes, once more!), amino acids (the building blocks of proteins), and proteins themselves, it is essential for almost all facets of plant growth. A plant lacking sufficient nitrogen is like a car attempting to operate on an empty tank.

Usually, the symptoms of nitrogen deficit are rather more general:

- Often, you’ll notice a more consistent, general yellowing of the leaves, which usually starts with the older, lower ones. Nitrogen, like magnesium, is a mobile nutrient; hence, the plant will transfer it from older tissues to encourage new growth. Eventually, the whole leaf, including the veins, will turn pale green and then yellow.

- Classic indicators are stunted development and frail, spindly stems. The entire plant might simply seem weak, sickly, and pale.

You may be asking, “Why include nitrogen if we’re discussing green veins?” An overall nitrogen deficit can occasionally start with the lower leaves yellowing in such a manner that the veins momentarily seem greener in contrast to the fast yellowing tissue, even if the classic, sharp interveinal chlorosis (distinct green veins, very yellow tissue between) points more strongly to magnesium or iron. Magnesium or iron, on the other hand, are more likely main suspects if the veins are clearly green and the interveinal regions are obviously yellow. We mention nitrogen here since it’s such a frequent lack that leads to great yellowing, and it’s nice to be able to tell it apart.

Among the usual causes of nitrogen deficit are:

- Soils lacking organic content. A major nitrogen source is organic material.

- Especially in sandy soils, heavy rain or over-irrigation can leach nitrogen from the root zone.

- Using very high carbon mulches—such as fresh sawdust or wood chips—without adding additional nitrogen can momentarily bind soil nitrogen. Soil microbes use nitrogen to assist in decomposition of the carbon-rich material, therefore competing with your plants for it.

Manganese (Mn) or zinc (Zn) could be candidates. Though less frequent, it is conceivable.

Although magnesium, iron, and nitrogen are the most common culprits, it’s important to note that shortages in other micronutrients including manganese (Mn) or zinc (Zn) can occasionally result in interveinal chlorosis.

- Often resembling iron deficiency, manganese deficiency causes yellowing on younger leaves while the veins remain green. On the other hand, it could also be followed by leaf necrotic (dead) patches or speckling.

- Usually on younger leaves, zinc deficit might cause stunted growth, abnormally tiny leaves—a condition sometimes known as “little leaf” syndrome—and interveinal chlorosis. You may also observe “rosetting,” which gives the plant a bunched-up look as the internodes—the spaces on the stem between leaves—are extremely short.

A small note here: For the typical home gardener, these (Mn and Zn deficits) are usually less common than problems with magnesium, iron, or nitrogen, but it’s good to have them on your radar for completeness, particularly if other remedies aren’t effective.

Playing Plant Detective: How to Identify the Correct Deficiency

Alright, I see the list of suspects. This is useful, but how do I focus it down to the actual culprit assaulting my prized tomatoes? Your sharp gardener’s eye comes into play here! Let’s wear our detective caps.

First: Site, Site, Site! Old vs. New Leaves: A Major Clue!

Often, this is the most vital first hint. Consider whether the yellowing with green veins mostly begins on the older, lower leaves of the plant. Should this be the case, it strongly suggests a lack of a mobile nutrient—one the plant can transfer. Your main suspects are Magnesium (traditional interveinal chlorosis on lower leaves) or, if the yellowing is more general and consistent, Nitrogen.

Is the issue, though, obviously showing on the newer growth tips and upper leaves? Should this be true, you are probably coping with an immobile nutrient—one the plant cannot simply move from older tissues. Especially if the veins are quite green, iron is the main suspect here. Deficiencies in manganese or zinc also appear on fresh growth.

Step 2: Look Closely at the Yellowing Pattern

Is it a very clear, sharp contrast between dark green veins and bright yellow tissue in between them? Seen on new leaves, this is characteristic of Iron deficiency; seen on older leaves, it is Magnesium deficiency.

Does the yellowing indicate a general paleness or a consistent yellowing that progressively covers the whole leaf, including the veins? This is more common with a Nitrogen deficit.

Do any other accompanying symptoms exist? Look for things like mottling (blotchy patterns), spots, leaf curling (upwards or downwards), or any unusual purpling of the stems or leaves. These could offer more hints. For example, upward curling with magnesium deficit, or purpling which can occasionally suggest phosphorus problems (although that typically doesn’t show as interveinal chlorosis).

Step 3: Think About Recent Care & Your Soil’s Story; Context Is Everything!

Especially for iron, soil pH is absolutely essential. Are you aware of the pH level of your soil? Now is a great moment if you haven’t ever (or in a long time) tested it. Most garden centres sell straightforward home test kits; for a more precise reading, mail a soil sample to your neighborhood cooperative extension office or a reliable soil testing laboratory.

- High soil pH (alkaline, usually above 7.0 or 7.2) makes iron deficiency quite likely since alkaline conditions “lock up” iron, rendering it inaccessible to plants.

- Magnesium deficiency is more likely if your soil pH is low (acidic, say below 6.0) or your soil is quite sandy since magnesium leaches more easily from acidic, sandy soils.

Consider how you water. Think about your watering practices. Leaves can turn yellow from both overwatering (which can cause root rot and hinder nutrient absorption) and extreme underwatering (which stresses the plant), sometimes resembling deficiency symptoms. Do your tomatoes grow in well-draining soil?

How about your past with fertilizer? If anything, what have you recently fed your tomatoes? Did you use a balanced fertilizer or something particular that could be high in one nutrient but low in others? Knowing that excessive one nutrient can occasionally interfere with the absorption of another (such high potassium blocking magnesium absorption) helps one.

Step 4: Test if unsure! Soil or Leaf Analysis for the Pros

Especially if the issue is widespread or continues despite your best efforts, think about getting a soil test for the most accurate and definitive diagnosis. Your local extension office, as noted, is quite helpful. This will indicate the pH and the concentrations of several nutrients in your soil.

Leaf tissue analysis can be done in certain situations, especially for commercial farmers or very passionate gardeners. This means sending a sample of the impacted leaves to a laboratory to ascertain the precise nutrient levels inside the plant tissue. The most straightforward approach to verify a suspected deficit is this.

Usually, by closely watching your plants and taking into account these elements, you can create a rather good educated guess about what is happening.

How to Feed Your Hungry Tomatoes & Fix Deficiencies: The Rescue Mission

Diagnosis finished (or at least, a strong hypothesis formed)! How do I get my cherished tomatoes back on the green track and flourishing again? The time has come for the action plan. Keep in mind that the aim is to act quickly yet gently. When it comes to fertilizers, more is not always better.

Magnesium (Mg) Deficiency Solution Set

Should your detective work indicate insufficient magnesium (yellowing with green veins on older, lower leaves, particularly in sandy or acidic soil):

- Immediate Relief: Foliar Spray with Epsom Salts

- A foliar spray is one of the quickest methods to deliver magnesium into your plant. In a gallon of water, dissolve 1 to 2 tablespoons of Epsom salts (magnesium sulfate). Spray this solution directly onto the leaves of your tomato plants, making sure it covers both the tops and undersides well. What makes this so effective? The plant can absorb the magnesium directly through its leaves, offering a far faster increase than waiting for roots to take it up from the earth. To prevent leaf scorch, do this on a cloudy day or in the evening.

- Soil Drench

- You can also water the soil surrounding the base of your plants with the same Epsom salt solution—1-2 tablespoons per gallon of water. This will let the roots have magnesium.

- Building a Magnesium-Rich Foundation: Long-Term Soil Health

- Should your soil test show acidity and low magnesium, think about dolomitic lime amendment. This is a wonderful option since it will also assist to increase the soil pH to a more tomato-friendly level and it offers magnesium as well as calcium. Follow soil test advice.

- You may add magnesium sulfate (Epsom salts) or a product like Sul-Po-Mag (sulfate of potash-magnesia, sometimes known as K-Mag) straight into the soil if your soil pH is already in a suitable range but magnesium is low.

- Good quality compost will help to increase your soil’s organic matter level as usual. Many kinds of compost are naturally high in magnesium and other necessary nutrients.

Iron (Fe) Deficiency Solution Set

Should the symptoms indicate iron deficiency—yellowing with green veins on the new, upper leaves, particularly if your soil is alkaline—then:

- Immediate Relief: Foliar Spray with Chelated Iron

- For foliar spraying, you’ll want a chelated iron product for iron. Why chelated, you say? “Chelated” refers to the iron being attached to an organic molecule maintaining its soluble, plant-available form, particularly under alkaline circumstances where iron would typically become inaccessible. This allows the plant to absorb far more through its leaves. Look for goods with Fe-DTPA or Fe-EDDHA; the latter is usually reddish-brown and quite good in high pH soils. For mixing and application rates, always follow the product label directions closely.

- Soil Application

- Some chelated iron products are also designed for soil application. Once more, adhere to the packaging instructions.

- Long-Term Soil Health: CRUCIAL for Iron Problems!

- Gradually lowering your soil pH will be the most sustainable, long-term remedy for iron deficit brought on by high pH. This isn’t a quick fix, but it’s the best approach. Materials including elemental sulfur, sphagnum peat moss, and other acidifying chemicals can help you to improve your soil. If at all feasible, include these into the soil well before planting. Changing soil pH takes time—often several months or even a season, so be patient.

- Including lots of organic material and compost helps as well. Organic matter enhances general soil structure and health and helps to chelate naturally occurring iron, therefore increasing its availability.

Nitrogen (N) Deficiency Solution Set

Pointing to a nitrogen deficit if your plants are exhibiting overall yellowing (especially older leaves first) and stunted growth.

- Rapid Fix: Fast-Acting Nitrogen Boost

- For a rapid nitrogen boost, liquid fertilizers are excellent. Choices include a balanced liquid fertilizer with a fair amount of nitrogen (the first number in the N-P-K ratio), blood meal combined with water, or fish emulsion (a little stinky but great for plants!).

- Though use them carefully as they can be strong and possibly acidify the soil over time if used excessively, some granular quick-release fertilizers like ammonium sulfate can also offer a quick nitrogen increase.

- Long-Term Soil Health (Creating Nitrogen Reserves)

- Make well-rotted manure and compost your closest friends! The greatest approach to increase general soil fertility and create stable nitrogen reserves is by regularly amending your soil with these organic powerhouses.

- Think about using pelleted organic tomato fertilizers, alfalfa meal, or feather meal among slow-release organic fertilizers. Over time, these slowly decompose to offer a consistent nitrogen supply.

- Planting legumes like clover or vetch can really “fix” nitrogen from the atmosphere and add it to your soil when they are tilled in if you practice cover cropping in your garden during the off-season.

Beyond the Quick Fix, Smart Fertilizing for Thriving Tomatoes

Although these focused remedies are excellent for handling particular deficits, let us not lose sight of the larger picture of maintaining your tomatoes happy and well-fed all through their growing season.

- Balanced Diet is Key: Remember that tomatoes need a wide spectrum of nutrients, not just N, P, and K, but also micronutrients including magnesium, iron, calcium, boron, etc. Don’t ignore other problems; instead, concentrate on resolving one.

- Understand Your Fertilizer Numbers (N-P-K): Take a time to grasp what those three figures on fertilizer bags signify. They show the proportion of N (Nitrogen), P (Phosphorus—as P₂O₅), and K (Potassium—as K₂O). Nitrogen encourages leafy growth; phosphorus is absolutely necessary for root development, flowering, and fruiting; potassium is essential for general plant health, disease resistance, and fruit quality.

- Feed at the Appropriate Times: Your tomatoes’ nutritional needs can shift with age. As seedlings, they’ll need a good start; before fruiting, they’ll need support for vegetative growth; as they start to set and ripen fruit, they’ll usually need a little more potassium.

- Organic vs. Synthetic: Your Decision; Both Have Advantages and Disadvantages. Generally speaking, organic fertilizers—such as compost, manure, fish emulsion, bone meal—release nutrients more slowly, nourish the soil life, and enhance soil structure over time. While they don’t significantly enhance long-term soil health, synthetic fertilizers give nutrients in a readily available form for rapid plant absorption. Many gardeners believe a mix approach is effective.

- Read those labels always, always! This is really crucial. Resist the urge to believe “more is better.” Over-fertilizing can be far worse than under-fertilizing, leading to “fertilizer burn” (damaged roots and scorched leaves) or nutrient imbalances that can cause even more problems. Stick to the product packaging’s application rates and directions.

Keeping Tomatoes Nourished from the Start: Prevention is Always Better Than a Cure

“Sure, I’m happy I know how to solve these issues, but next year I’d much rather not be emergency plant doctor! How can I stop these nutrient deficits from occurring initially?” The key to a stress-free (well, less stressful) gardening season is proactive care.

Everything is soil; begin with a good basis.

- Test and Amend Soil Before Planting: Before planting, test and amend your soil; this is the golden rule of effective gardening. Knowing your soil’s pH and current nutrient levels lets you to make any required changes even before you put a single tomato plant in the ground. Correcting problems proactively is so easier.

- Compost, Compost, Compost: Experienced gardeners will tell you to compost, compost, compost since they have good cause to do so. For the gardener, compost is black gold. Whether your soil is free-draining sand or heavy clay, compost improves its structure, increases water retention, promotes beneficial microbial activity, and more importantly, gradually releases a wide range of vital nutrients for your plants. Every year, make it a practice to include lots of good quality compost into your tomato beds.

- Consistent Watering: Tomatoes flourish on steady moisture. Steer clear of wild swings between bone-dry circumstances and soggy, waterlogged soil. Both extremes can tax the plant and compromise its capacity to absorb nutrients. Instead of shallow, regular sprinkles, shoot for deep, infrequent watering.

- Mulch Your Plants: Applying a 2-3 inch layer of organic mulch—such as straw, shredded leaves, or grass clippings—around your tomato plants is a great practice if they haven’t been treated with herbicides. By lowering evaporation, mulch helps to keep consistent soil moisture; it also suppresses weeds (which would otherwise compete with your tomatoes for water and nutrients! ), keeps the soil cooler in summer, and may even contribute more organic matter and nutrients to the soil as it gradually breaks down.

- Think about crop rotation: If at all feasible, avoid planting tomatoes (or their near relatives in the nightshade family, including peppers, potatoes, and eggplant) in the precise same location in your garden year after year. Rotating your crops not only helps to prevent the depletion of particular nutrients that some plants draw heavily upon but also helps to lower the accumulation of soil-borne pests and diseases that can affect certain plant families.

Focusing on developing healthy, rich soil and offering regular care will help you to greatly lower the likelihood of your tomatoes lacking nutrients.

Wait, maybe it’s something different. When Yellow Leaves Aren’t a Hunger Pains

Although nutritional deficits are quite frequent causes for the “yellow leaves with green veins” appearance, particularly interveinal chlorosis, it’s important to keep in mind that occasionally other elements may be involved. Just pause to think about these other options before you go all-in on fertilizers:

- Watering Woes: As we discussed, both overwatering (which can cause oxygen-starved roots unable to absorb nutrients properly and even root rot) and severe underwatering (which stresses the plant) can cause leaves to turn yellow. Before assuming it’s a nutrient problem, check the soil moisture a few inches down.

- Annoying Pests: Some unwanted visitors can induce yellowing. For example, spider mites are little insects that drain leaf sap, usually producing a stippled, yellowish look. A severe aphid infestation can also stress the plants enough to produce some yellowing. Examine the undersides of leaves closely.

- Sneaky Diseases: Some fungal or viral plant diseases can cause leaf yellowing. But these usually accompany other unique symptoms including leaf spots, wilting (usually beginning on one side of the plant or leaf first in the case of Fusarium or Verticillium), stem lesions, or aberrant growth.

- Environmental Stress: Tomatoes can be a little finicky about their surroundings. Plants can be stressed by extreme temperatures—both too hot and too cold for extended periods—or rapid, dramatic changes in weather conditions, which can cause yellowing leaves.

- Damaged roots (possibly from tilling too close, soil compaction limiting root growth, or root-feeding pests like nematodes) will impair the plant’s capacity to absorb water and nutrients, which may show as yellow leaves.

As always, the secret is close observation. Examine the entire plant, not only the yellow leaves. Think about the general growing circumstances and any recent changes. Should you have attempted to solve possible nutritional problems and the issue continues or does not exactly match the conventional deficiency patterns, it would be beneficial to look into these other paths.

From Yellow Flags to a Red Harvest, then!

That is all there is! Indeed, seeing those yellow leaves with clearly green veins on your tomato plants is a clear indication, a yellow flag, that your plant is attempting to convey something significant. Usually, it’s indicating a lack of a key nutrient; magnesium (showing on older leaves) or iron (showing on younger leaves) are the most frequent offenders for this particular trend. Occasionally, particularly if the yellowing is more general, a larger nitrogen problem may also be present.

But the amazing thing is, you are now empowered! You’re well-equipped to identify the issue by learning to notice the location and particular pattern of the yellowing, and by evaluating your soil’s qualities and your past care techniques. You have turned into a plant detective!

The greatest part is? Almost certainly, corrective action by means of targeted fertilization combined with a long-term dedication to developing healthy soil will restore your tomato plants to their lively green, productive selves. Though it could require some patience, the benefit—a garden full of healthy, thriving tomato plants and the tasty, sun-ripened fruits they offer—is well worth the work.

Happy gardening, and here’s to a garden bursting with a red harvest!

Your Tomato Troubleshooting FAQ

Let’s address some often-asked questions still possibly on your mind:

Q1: Can I simply apply a general all-purpose fertilizer to remedy yellow leaves with green veins? A: It could be useful if it’s a broad, general deficit, or if the all-purpose fertilizer fortuitously includes the particular nutrient your plant lacks in a sufficient quantity. A general fertilizer might not properly address the root cause, though, if a high soil pH is causing a very particular deficiency of, say, iron. Often, much better and more efficient is focused action following a thorough diagnosis. You don’t want to overfeed your plant with other unneeded nutrients.

Q2: After I fertilize my tomatoes, how quickly will they actually improve? A: The nutrient, the degree of the deficit, and your fertilizer application will determine this. You might begin to notice a small change in the new growth within a few days to a week using foliar sprays—like Epsom salts for magnesium or chelated iron. Though new leaves should seem greener, the older ones may not fully recover. Soil corrections, particularly those involving pH changes, take far longer to produce results—think weeks or even months. A gardener’s quality is patience!

Q3: Can I overfertilize my tomatoes? Can I go too far? A: Of course, yes! This is rather typical error. Over-fertilizing your plants might cause “fertilizer burn,” which harms their roots and burns their leaves. It can also lead to nutritional imbalances that aggravate even more issues than the initial lack. Always, always adhere to the application rates and directions on the product label; if you ever have doubt, it’s usually safer to err on the side of using a little less rather than too much.

Q4: Should I take off the yellow leaves from my tomato plant? A: Yes, it’s usually a good idea to remove them if leaves are significantly yellowed and obviously past their prime. They can occasionally turn entry points for illnesses or pests and are not really increasing the energy output of the plant. Use sharp pruners or snap them off at the stem to remove them cleanly. Removing the yellow leaves, though, does not address the root issue. So that new leaves grow in healthy and green, your primary emphasis should be on identifying and fixing the nutrient deficit.

Q5: My soil test findings indicated I have lots of iron in my soil, but my new tomato leaves remain yellow with green veins. What causes this? A: This is a typical situation that nearly always suggests a soil pH problem! As we talked about, should your soil pH be too high (alkaline), the iron may be in the soil but it’s chemically “locked up” and not accessible for your tomato plants to take. The test indicates it exists, but your plant cannot reach it. Your work in this situation should concentrate on either gradually lowering your soil pH (using elemental sulfur, peat moss, etc.) or foliar feeding with chelated iron to avoid the soil problem.

Q6: Where can I have my soil tested consistently and accurately? A: Usually, the best and most dependable source for soil testing is your nearby cooperative extension office, sometimes connected to a state university. Their reports usually include certain recommendations suited to your location and the kind of plants you wish to cultivate, and they provide thorough soil tests at fairly low cost. Though usually less accurate than lab tests, many respected garden centers also sell home soil test kits that can provide you a broad picture of your soil’s pH and occasionally significant nutrient levels.