The Ultimate Guide to Using Lilacs in a Modern Landscape.

Lilac’s smell is a strong way to travel through time. A single breath can take you to a grandparent’s garden, your childhood home, or a country road you haven’t been on in years. But for a lot of gardeners who care about style, that strong nostalgia is a double-edged sword. We adore the smell and the memories, but we’re not sure if we should plant one because we think the lilac is a “old-fashioned” plant that will seem out of place in a clean, modern setting.

It’s time to think of a new way to look at this classic. A lilac is more than just its two weeks of fragrant flowers. It is a powerful, architectural plant with a sturdy vertical structure and bark with an unusual texture that looks good in the winter. When positioned correctly, it can also make a thick, live screen for seclusion. A lilac may go from being a cute heritage to a stylish design feature that feels both timeless and completely modern with the appropriate choice, placement, and companions.

We need to think like designers and follow a few basic rules to do this.

- The Power of the Specimen: In modern design, less is frequently better. Instead of a flower garden full of flowers, picture a solitary, well-pruned lilac as a living sculpture. When you put the lilac against a clean architectural wall, in a sea of black gravel, or in a mass planting of a single, low groundcover, its shape becomes the star. The space around it makes its structure stand out, making it a strong focal point.

- The Effect of Repetition: One lilac can be a specimen, but a row of three or five identical lilacs becomes a part of the building. This planned repetition makes a powerful visual rhythm that feels current and purposeful. A row of lilacs can make a beautiful, fragrant hedge that defines an outdoor area, blocks an undesirable view of a neighboring property, or lines a driveway with a grand sense of arrival.

- The Contrast of Form: A lot of the time, good design is all about contrast. Lilacs look even better when they are next to plants that have a completely different appearance. Their erect, woody structure and delicate, spherical flower clusters are stunning on their own. A lilac’s shape and the soft, mounding shape of an ornamental grass or the pointed, spiky leaves of a yucca make both plants more intriguing and active.

Expert Tip: I’ve seen people make the biggest error by putting a single lilac in the midst of a lawn, where it looks lost and like it was put there by accident. If you want to make it current, do it on purpose. Put a formal pair of them around a door frame, or use one well-pruned tree-form lilac as the main feature of a simple patio garden. The setting is everything.

A curated guide of the best lilac types for the job

Not every lilac is the same. The old common lilac, which used to grow all over the place, has been joined by several new types that have been bred to have better habits, cleaner leaves, and smaller sizes that are appropriate for modern gardens. The first step to success is choosing the proper one.

Best for Pruning Trees and Structures

You need a variety with naturally erect stems and strong stems to make a powerful vertical element or a beautiful multi-stemmed tree.

- Syringa vulgaris ‘Sensation’ is known for its unusual purple flowers with white edges and robust, vase-like shape.

- A classic, tall type with lovely, true blue flowers and a majestic look is Syringa vulgaris ‘President Lincoln.’

- The Japanese Tree Lilac, or Syringa reticulata ‘Ivory Silk,’ is a distinct species. It is a true single-stem tree that blooms later and has large panicles of creamy white flowers. It is a great pick for a modern, formal specimen.

Best for Small Spaces and Modern Gardens

Dwarf versions are a requirement for smaller yards, patios, or a neater look. Their thinner leaves and denser growth generally fit better with modern buildings.

- Syringa meyeri ‘Palibin’ is a small, spherical shrub with lavender-pink flowers that smell good.

- This plant, Syringa patula ‘Miss Kim,’ is known for its neat, upright growth, clean leaves, and beautiful, fragrant, icy-blue flowers that bloom a little later than conventional lilacs.

- Bloomerang® Dwarf Purple is a part of the reblooming line. It stays around 3 feet tall and broad, so it’s great for containers or the front of the border.

Best for Not Getting Sick (No More Powdery Mildew)

Many older lilacs hate powdery mildew, which is a dusty white fungus that shows up in damp weather. The greatest way to keep your look clean and current is to get a resistant variety.

- Preston Hybrids (S. x prestoniae): This group, which includes ‘Miss Canada’ and ‘James Macfarlane,’ is quite hardy and doesn’t get mildew easily. They bloom a few weeks after regular lilacs.

- The “Pocahontas” hybrid is a deep violet lilac that blooms early and is very resistant to mildew.

- “Miss Kim”: This type is recognized for its clean, disease-free leaves all season long, in addition to being little.

Expert Tip: I typically suggest the reblooming Bloomerang® Dark Purple for a really trendy look. It has thinner leaves, a neat, rounded shape, and lots of rich purple flowers that bloom over and over again. It looks much more modern than the original common lilac, and it grows well without turning lanky.

Planting and soil: the key to success

Lilacs are resilient and can grow in many different places, but they need two things to grow well: full sun and the proper soil pH.

First, they need at least six hours of direct sunlight every day that isn’t filtered. This isn’t a suggestion; it’s a rule. The light gives the plant the energy it needs to photosynthesize, which makes the sugars that make a lot of flower buds. A lilac in the shade may live, but it will be a lush green disappointment with few or no flowers.

When you plant, make a hole that is twice as wide as the root ball but not deeper. This makes it easy for the roots to spread out into the soil around them. Carefully put the plant in the hole, making sure that the top of the root ball is level with or slightly above the soil around it. Fill in the hole with the native soil and water it well to get rid of any air pockets.

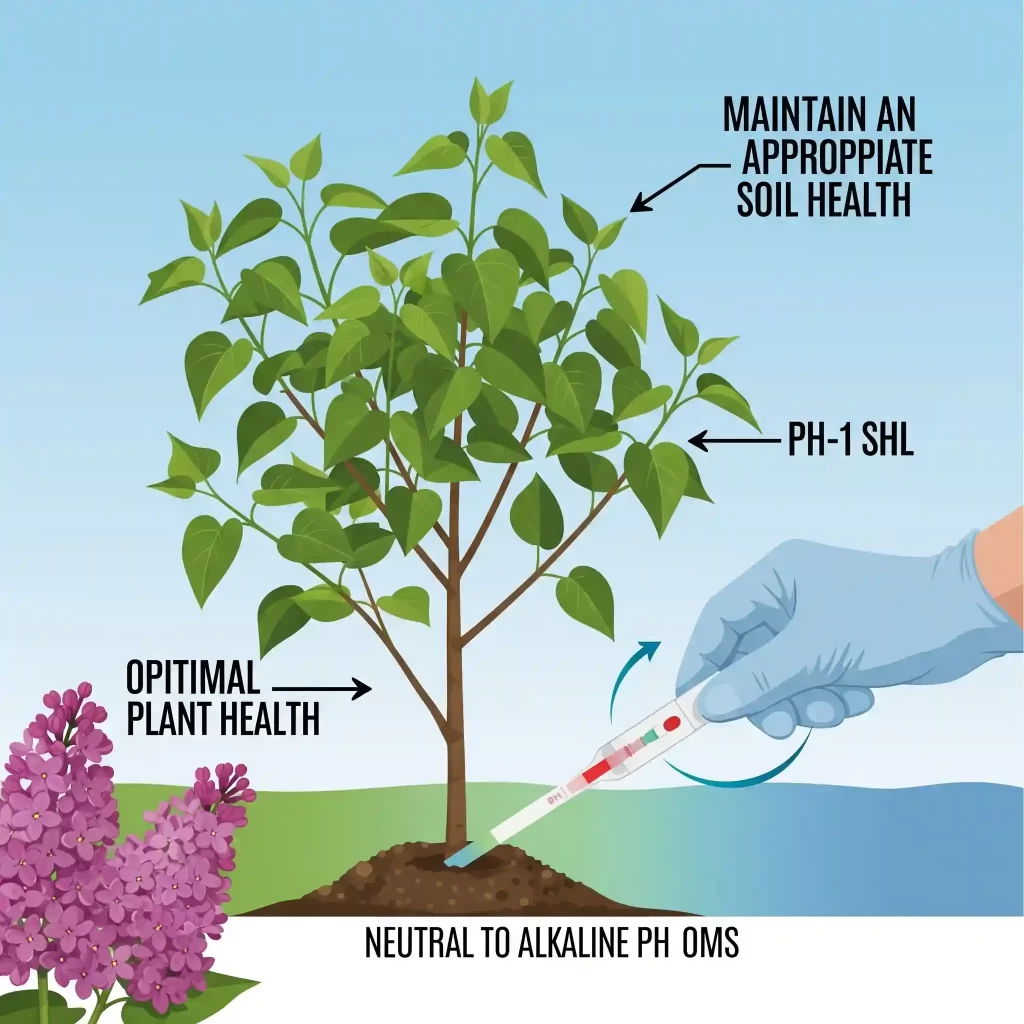

The Alkaline Advantage: The Secret to Great Blooms Is Soil pH

Here’s a bit of gardening science that tells the difference between sickly lilacs and beautiful ones: lilacs do best in soil that is neutral to slightly alkaline (with a pH of 6.5 to 7.5).

In a lot of places in the country, especially where it rains a lot and there are coniferous forests, the soil is naturally acidic (a pH below 6.5). Essential minerals, especially phosphorus, which is very crucial for flower formation, get “locked up” in acidic soil. The nutrients are in the soil, but the plant’s roots can’t take them in. This is why your green lilac plant could be big and robust yet never flower. It requires more nutrients to develop blossoms, and it’s not getting them.

A local university extension office can provide you an accurate soil test to help you figure out what’s wrong. You can do a simple test at home by putting a sample of soil in a jar and adding a dash of vinegar. Your soil is alkaline if it fizzes. If not, put a new sample in a different container, add a little water to produce mud, and then sprinkle baking soda on top. Your soil is acidic if that fizzes.

If you find out that your soil is acidic, you can fix it by adding dolomitic garden lime in the fall. Over the winter, using lime will progressively raise the soil’s pH, which will make nutrients available to your lilac in the spring. Carefully read the instructions on the product packing.

One mistake people often make is planting a lilac directly near to a foundation. The concrete leaches lime into the soil, which makes it quite alkaline (which lilacs adore), but the wall hinders air flow. Powdery mildew loves this still air since it is a great place to grow. To let air travel freely between the branches of your lilac, it should always be at least 5 to 6 feet away from any wall or substantial fence.

Pruning for a Reason: From Basic Upkeep to Major Renewal

People often don’t understand how to prune lilacs, but it’s the best way to shape a plant that looks well in a modern setting.

The Golden Rule is easy to remember: prune your plants two weeks after the blossoms have died. During the summer, lilacs make bloom buds for next year on this year’s growth, which is called “old wood.” If you prune before the flowers bloom in the fall, winter, or spring, you will cut off all of next year’s blossoms. The easiest thing to do is to deadhead the flower trusses that have already bloomed. To do this, cut slightly above the first set of leaves.

But we need to go deeper to really make a difference in design.

The 3-Year Plan to Make an Overgrown Monster Look New Again

Don’t worry if you’ve gotten a huge, lanky lilac that only flowers at the top. This step-by-step method will help you thoroughly rejuvenate it.

- Year 1 (Late Winter): Find the oldest, thickest stems with bark on them. Pick one-third of them and use a sharp pruning saw to cut them down to about 6 to 12 inches from the ground. It will feel harsh, but this will make fresh, strong shoots grow from the base.

- Year 2 (Late Winter): Choose another third of the old stems that are still there and chop them down to the ground. You will see new growth where you cut last year.

- Year 3 (Late Winter): Cut down the rest of the old stems. By the end of this year, your shrub will be completely new, with stems that are 1, 2, and 3 years old, a much better form, and blossoms that are at a height you can enjoy.

How to Turn a Lilac into a Pretty Little Tree

This method changes everything, converting a regular shrub into a show-stopping beauty.

- Start with a young, healthy plant or one that has been revived and has a lot of strong, upright stems.

- Choose three, four, or five of the best-spaced, most vertical stems to be your main “trunks.” Cut off all the other stems at the ground level.

- Slowly cut off all the lower side branches from your chosen trunks until they are 4 or 5 feet tall. Cut cleanly and just outside the “branch collar,” which is the slightly swollen area where the branch meets the trunk.

- For the following few years, keep cutting off any new suckers and low-growing side branches at the base to keep the trunks free. After each year’s blossoming, shape the upper canopy as needed. The end result is a magnificent tree with many stems, attractive bark, and a light canopy.

The Best Way to Keep Powdery Mildew Away Is to Prune for Airflow

You may cut down on the chance of powdery mildew by a lot by thinning out the core of a healthy lilac shortly after it blooms. Just reach into the middle of the plant and pull out those branches that are crossing, rubbing, or developing toward the center. This simple step lets air and sunlight into the plant, which speeds up the drying of the leaves when it rains and keeps fungal spores from taking hold.

Expert Tip: After you finish your primary pruning, always check the base of the plant for suckers and cut them out. These are usually from the original rootstock (particularly on grafted types) and won’t make flowers as good as the main shrub. Cleaning the base keeps the plant’s shape and health as it should be.

The Modernist’s Palette: Planting with Friends for a Modern Look

To break the cottage garden mold, you should mix your lilac with plants that are surprising and bring out its shape, texture, and color palette.

For Structure and Contrast

Put the lilac’s gentle, romantic shape next to straight lines and powerful shapes.

- Alliums: The big, round flower heads of “Globemaster” or “Purple Sensation” Allium are a beautiful reflection of the lilac’s color in a modern way.

- Boxwoods: The crisp, clipped lines of evergreen boxwood spheres or low hedges planted in front of a lilac make a wonderful contrast between formal and informal, wild and controlled.

- Feather Reed Grass (‘Karl Foerster’): The long, slender, vertical plumes of this grass are a great contrast to the rounded shape of the lilac shrub. They add movement and a modern look.

For a Simple, Cool Color Scheme

Stick to a cool color scheme to make a calm and classy vignette.

- Lamb’s Ear (Stachys byzantina): The soft, silver-gray leaves make a lovely groundcover that doesn’t need much care at the base of a purple or white lilac.

- Russian Sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia): The lavender-blue flowers and hazy, silvery stalks of Russian Sage bloom later in the summer, adding to the cool color narrative.

- Blue Fescue (Festuca glauca): Small mounds of icy-blue, spiky grass add a great texture and keep the cool color scheme going at the ground level.

To Keep Things Interesting All Year

Even when things aren’t blooming, a modern garden looks nice. These partners make sure that the neighborhood surrounding your lilac is always intriguing.

- Coral Bells (Heuchera): Plant these under a tree-like lilac. The colorful leaves of Heuchera, which come in rich burgundy, chartreuse, or silver, add interest from spring to fall.

- Autumn Sedum (‘Autumn Joy’): This sedum has heads that look like broccoli in the summer and open to pink flowers in the fall. In the winter, the dried seed heads give it a robust structure.

- Japanese Anemones: These beautiful flowers with long stems bloom in late summer and fall, giving a second, delicate wave of color long after the lilac has gone.

Why isn’t my lilac blooming? Troubleshooting (And Other Problems That Happen Often)

This is the question that people ask the most about lilacs. One of these six things is almost always the answer. Use the checklist to figure out what’s wrong with your plant.

- Not Enough Light? This is the main cause. A lilac needs at least six hours in direct sunlight every day. The solution is to move the plant to a sunny spot in the fall or pay an arborist to cut back tree branches that are hanging over it.

- Cutting at the Wrong Time? Did you or a landscaper cut it back in the fall or winter? The Fix: Wait. Don’t cut it back this year. After it blooms next spring, cut it back the right way.

- Is there too much nitrogen? Is your lilac planted in or near a lawn that gets a lot of fertilizer? The “N” in N-P-K stands for nitrogen, which is what lawn fertilizers are high in. This makes leaves grow thick and flowers bloom less. The solution is to stop using any fertilizer with a lot of nitrogen near the plant. In the fall, you can use a fertilizer with more phosphorus (the “P”), like bone meal, to help future blooms.

- Is it old enough? It may take a newly planted lilac two to three years to have a robust root system before it can blossom a lot. The Fix: Be patient and give it regular water for the first few years.

- Is it too old? Is your lilac a thick, woody tangle of old stems with leaves just at the top? The aged timber is no longer strong. The Fix: We need to make a change. Put into action the three-year rejuvenation pruning plan that was talked about above.

- Is your soil too acidic? If your leaves are green and thick but there are no blossoms, and you’ve checked out other problems, your soil’s pH is probably the problem. The Fix: Check the soil. If it is acidic, use garden lime in the fall as instructed.

In conclusion

The lovely lilac, with its sweet smell and generous nature, should be in every garden, even the newest ones. If we stop thinking of it as a fussy old thing and start thinking of it as a flexible, structural plant, we may see its actual potential. The lilac changes through careful positioning as a specimen, the architectural strength of repetition, and purposeful pruning that shapes it into a beautiful shape. When paired with modern companions that value contrast and texture, it shows that it is much more than a two-week wonder. It is a living sculpture, a classic that never goes out of style, and a feature that lasts all year.

Questions that are often asked (FAQ)

How close to my house can I put a lilac?

You should grow a lilac at least 5 to 6 feet away from your house or any other substantial wall. They love the alkaline soil near concrete, but they need good air flow to keep powdery mildew from growing. The greatest way to protect yourself is to give them space.

Do lilacs that bloom again need different care?

The Bloomerang® collection of reblooming plants is special because they bloom on both “old wood” (from the first flush of spring) and “new wood” (later in the summer). This means you can cut them back just after they bloom for the first time without losing the following blooms. A little shaping at that time can help the plant bloom again more heavily.

How do you get rid of powdery mildew the best?

The greatest way to treat something is to stop it from happening in the first place. Pick a variety that is resistant to disease, allow it lots of sun and room to breathe, and utilize the thinning pruning method that was talked about above. If you do develop mildew, you can use horticultural oil or a DIY spray composed of one tablespoon of baking soda and half a teaspoon of liquid soap in a gallon of water. However, it’s preferable to focus on prevention.

Do deer stay away from lilacs?

Yes, in general. Deer don’t like to eat lilacs, and they usually choose other plants like hostas or tulips instead. But if deer are really hungry and under a lot of stress, no plant is 100% deer-proof.

Can I put a lilac in a big modern planter?

Yes, but you have to pick a real dwarf type, like “Miss Kim” or one from the Bloomerang® Dwarf series. To give the roots ample room, you will need a container that is at least 24 inches wide. Keep in mind that plants in containers need to be watered and fertilized more often than those in the ground.