What do the seeds of lilacs look like? A Full Visual Guide to Growing from Seed

TL;DR

- Finding Seeds: Lilac seeds are found inside small, oval pods that form after the flowers fade. You must wait until late fall to harvest these pods, after they have turned from green to a dry, leathery brown and begin to split open on their own.

- Seed Appearance: A lilac seed is a small, flat, brown kernel, similar in size to a grain of rice. Its most distinct feature is a papery, wing-like structure called a samara, which helps it travel on the wind.

- Genetics Warning: Seeds from a named hybrid lilac (e.g., ‘Sensation’) will not grow “true to type.” The resulting plant will be a genetic lottery, a unique offspring of the parent and whichever other lilac pollinated it. It will not be an exact clone.

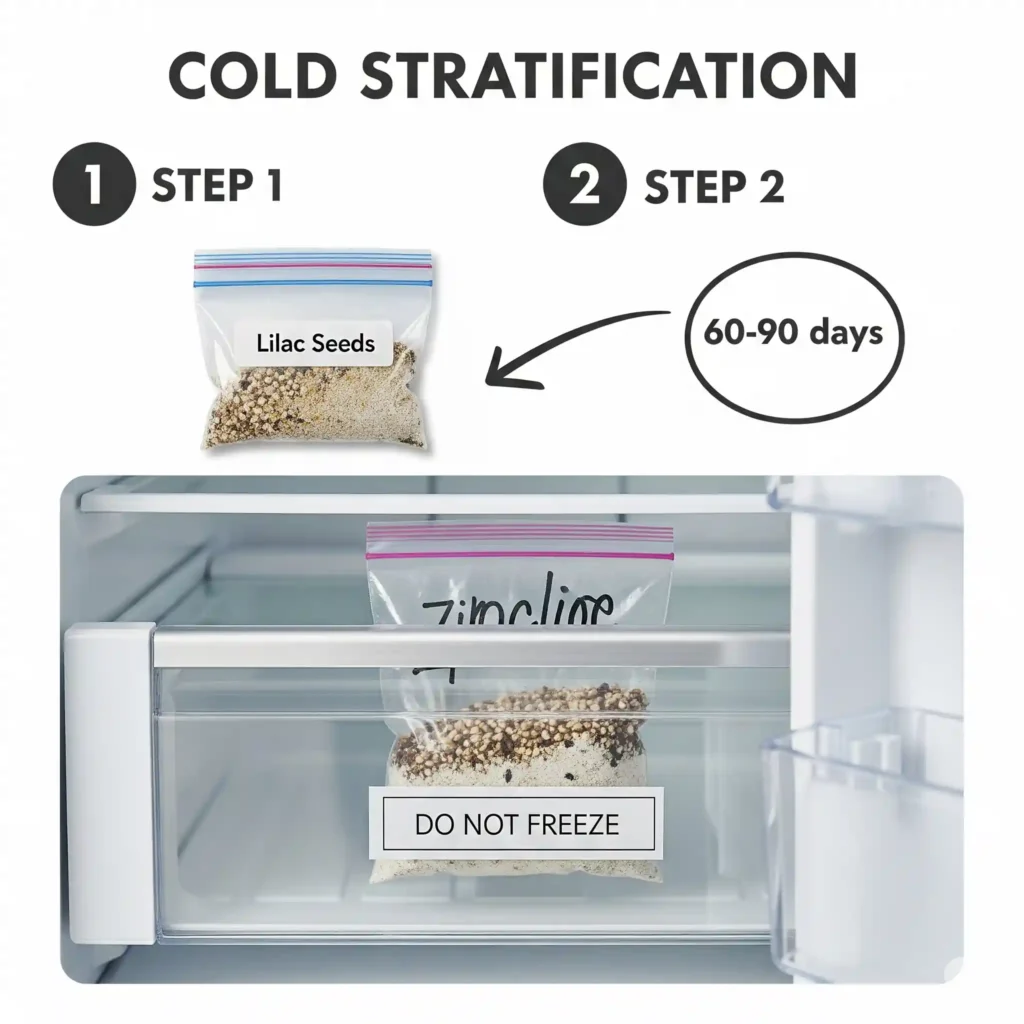

- Stratification is Mandatory: Lilac seeds have a natural dormancy. To break it, they require cold, moist stratification. This involves mixing the seeds with a damp medium (like sand or vermiculite) in a sealed bag and refrigerating it (not freezing) for 60 to 90 days.

- Patience is Required: Growing a lilac from seed is a very slow process. It can take 4 to 7 years for the seedling to produce its first flower. For faster, identical clones, use methods like cuttings or transplanting suckers.

The Journey from Flower to Seed Pod

A new, calmer process starts after the beautiful, aromatic show of a lilac in full bloom has vanished. You might see the old flower trusses progressively change, forming groups of little, green pods where the flowers used to be. This makes a natural query for the curious gardener: What’s inside? And can I use it to grow a new lilac?

Yes, but it takes time, science, and a little bit of uncertainty to get from that seed pod to a flowering bush. This guide is meant to be the most complete source of information on the subject. We will provide you more than just a basic description. We will give you a full visual guide to finding lilac seeds, a lesson in the science of how they grow, and a realistic timeframe for what to expect. This is the best handbook for gardeners who want to do something fun and gratifying over a long period of time.

A Picture Book on the Journey from Flower to Seed

First, you need to know the whole life cycle of the lilac’s reproductive components in order to find the seeds. The procedure happens slowly over the summer and fall.

- The Faded Flower Truss: In late spring, after the flowers have been pollinated, they will wither and fall off, leaving behind the green framework of the flower head. This is where the process starts. At this point, a lot of gardeners deadhead their lilacs to achieve better blooms next year. However, if you want seeds, you need to leave the dead flower heads on the shrub.

- Growing Green Pods: In the next few weeks, you will notice small, green, flat oval pods start to grow where the individual florets used to be. These are the immature seed capsules. The seeds inside are still growing and can’t be used yet.

- Mature Brown Pods: These green pods will steadily grow and develop over the summer. They will acquire a dry, leathery, dark brown color by the end of summer and into the fall. This is the most important stage of ripening. You have to leave the pods on the bush until they are completely dry.

- The Split Pod: When the mature pods dry up, they will start to split apart along a seam, showing the seeds inside. On a dry, windy day, you could even see the seeds start to fall out of the pods on their own.

- The Seeds: You can view each seed after they are discharged. Each one has a little, flat kernel with a light brown wing that looks like paper. The whole thing is called a samara.

Tip from an expert

Don’t give in to the urge to pick the pods when they are still green. The seeds within are not ready to grow yet. You have to wait until late fall, when they are dried and leathery brown and you can hear the seeds rattling within when you shake a limb. Be patient.

What do the seeds of lilacs look like? A Detailed Identification

A lilac seed is a natural engineering wonder that is made to spread by wind. The seed is a small, brown, flat kernel that is usually no bigger than a grain of rice. The pale, papery wing, or samara, that is linked to it is what makes it stand out the most. This wing works like a helicopter’s blade, letting the seed spin and move with the wind. It takes the seed away from the parent plant to find a new spot to grow.

Plants often use this structure as a strategy. You will see the same basic shape in a lilac seed as you would in the spinning “keys” of a maple tree or the winged seeds of an ash tree. The seeds of different lilac species may be a little different in size. For example, the seeds of a giant Tree Lilac (Syringa reticulata) are much bigger than those of a common lilac (Syringa vulgaris). However, they all have the same basic winged shape.

The Genetics of Lilac Seeds: What to Expect from Your New Plant

Before starting this endeavor, a gardener should know that seeds from a labeled hybrid lilac will not grow “true to type.” This is perhaps the most crucial thing for them to know. This means that the plant that grows from this will not be a perfect copy of its parent. To keep your hopes in check, it’s important to know the basic genetics behind this.

The Parent Comparison

A named hybrid lilac, like the well-known “Sensation” (which has purple florets with white edges), is like a person with a certain set of genes. The seeds are like its kids. Like how kids have traits from both parents and don’t look exactly like either one, the seeds from your “Sensation” lilac were made when another lilac, maybe a typical purple one down the street, pollinated its blossoms. The seedling that comes from this will have an entirely fresh and random mix of genes from both parents. It could have simple purple flowers or a new color pattern that no one else has. It could be pretty, but it won’t be a “Sensation.”

Heirlooms or hybrids?

Seeds from a non-hybrid species lilac, like the wild Syringa vulgaris, are more likely to look like the parent plant because their genes are more stable and they are more likely to have been pollinated by a plant that is genetically identical to them. But there can still be some natural diversity in these species.

From what I’ve seen, growing a lilac from seed is like playing the genetic lottery. You could end up with a beautiful new flower with a smell and color that has never been seen before, or you could end up with a simple, faded lavender blossom. The fun is in the surprise and the process, not in trying to make a copy of your plant. You have to utilize alternative ways, such cuttings or rooted suckers, if you want an exact clone.

A Masterclass in Planting Lilacs from Seed

To get a lilac seed to grow, you have to follow a certain set of measures to break the seed’s natural dormancy and get it to grow. This takes a long time but is worth it.

Step 1: Gathering and Taking Out

Pick the completely brown and dry seed pods in late fall on a dry day. Put them in a paper bag and keep them inside in a warm, dry place. In the next several weeks, you’ll hear the pods start to pop and break open, letting the seeds out. You can shake the bag to separate the seeds from the pod pieces (the chaff) once most of them have opened.

Step 2: The Science Behind Cold Stratification

This is the most important and scientific stage. Lilac seeds have a built-in way to stay dormant so they don’t sprout in the fall and die in the winter. To break this dormancy, they need to be in cold, wet circumstances for a lengthy time. Stratification is the process that makes the seed assume it has made it through winter and is now spring and safe to sprout.

Step 3: The Refrigerator Method (A Tutorial That Works Every Time)

This is the best technique to make sure the seeds have all they need.

- Add a handful of sterile, somewhat damp (not soaking wet) medium like sand, vermiculite, or peat moss to the seeds you collected.

- Put the whole mixture in a plastic Ziploc bag that is labeled and sealed.

- Put the bag in the fridge, preferably in the vegetable crisper. Putting it in the freezer will harm the seeds, so don’t do that.

- Put the seeds in the fridge for 60 to 90 days to stratify them. Put the start and end dates on your calendar.

Step 4: Planting the Seeds

It’s time to plant after the winter weather is over. Make a clean seed tray or small pots with a seed-starting mix that is sterile and drains properly. Put the stratified seeds in the ground approximately 1/4 inch deep and gently press down on the dirt.

Step 5: Care for the plants in the first year and germination

Put the tray in a warm, sunny place that doesn’t get direct sunlight. Don’t let the soil get too dry, but don’t let it get too wet. Be patient; germination can be sluggish and unpredictable, and it can take weeks. You can carefully move the seedlings into their own pots once they have their first set of real leaves. For the first year, keep them in a safe place because they will be extremely little and grow slowly.

- Common Mistake 1: Not stratifying. If you plant seeds that are warm and dry immediately into the ground, they will not germinate. They need a time when it’s cold and wet.

- Common Mistake 2: Putting the plants too deep. These tiny seeds don’t have a lot of energy stored up. If you put them too deep, they will run out of energy before the seedling can get to the surface and the sun.

- Common Mistake 3: Giving seedlings too much water. “Damping off” is a fungal disease that rots the stem at the soil line when it is too wet. It is quite easy for little seedlings to get this illness. Make sure the air can move around well and let the soil dry out a little bit between waterings.

The Long Journey: A Realistic Timeline from Seed to Flower

This method requires a lot of patience. If you want speedy results, don’t try to grow a lilac from seed. This realistic timeline can help you keep your hopes in check.

- Year 1: The year when seeds sprout and seedlings grow slowly. Your lilac seedling might only be a few inches tall at the end of the first growing season. Your main job is to keep it safe and watered.

- Years 2 to 3: The plant will start to look more like a tiny shrub. It is putting all of its energy into building a robust root system and making its woody structure. It will probably get to be around a foot or two tall.

- Years 4 to 7: The plant may make its first flower truss. This is a really important time! As the plant grows and matures, the number and size of the blossoms will get bigger each year.

A quick comparison of seeds and other methods

Knowing about different ways to propagate plants helps explain why growing from seed is a more specialized task.

| How | Result | Hardship | Quickness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seeds | A new, one-of-a-kind genetic person. Not a copy. | High. Needs to be stratified and requires a lot of time. | Very slow (it takes 4 to 7 years for the first flower to bloom). |

| Cuttings | A perfect copy of the parent plant. | Medium-High. It can be hard to get it to root. | Medium (2–3 years till the first blossom). |

| Suckers/Transplants | A perfect copy of the parent plant. | Simple. Digging up a rooted shoot is part of it. | Quick (1–2 years till the first blossom). |

Final Thoughts

Finding lilac seeds is a simple beginning step on what might be a long and interesting journey in gardening. Growing a lilac from seed is a one-of-a-kind way to make a clone of a favorite plant, even though alternative ways are faster and more reliable. It is a project for the patient gardener, a game of genetic chance that promises the ultimate reward: the possibility to produce a wholly new and unique plant, bringing a flower into the world that has never existed before.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I tell whether my lilac seeds will grow?

You can’t be 100% sure without a germination test, but you can do a simple “float test.” Put your seeds in a bowl of water. After a few minutes, people usually think that the seeds that sink are more likely to be viable since they are thicker and have a fully formed embryo inside. The seeds that float might not have anything inside them or might not be fully grown. This test isn’t perfect, but it can help you choose the best people to plant.

What is the difference between scarification and cold stratification?

Stratification is the process of putting a seed in cold, wet conditions for a while to break its internal dormancy, like in winter. For seeds like morning glories or sweet peas, scarification is the process of physically scratching or weakening the hard outer layer of the seed so that water may get in. Lilacs don’t need this.

Can I just plant the seeds in the fall right in my garden?

Yes, this is conceivable, and it’s called “natural stratification.” In the fall, you can sow the seeds in a garden bed that has been prepared. Nature will take care of the cold, wet time. But the success rate is generally substantially lower. Birds or rats can consume seeds, severe rain can wash them away, or they might not germinate because the moisture level is not stable. The controlled refrigeration method gives you a considerably better chance of success.

Do I have to cut off the dead blossoms on my lilacs to collect seed pods?

No, in fact, you have to do the opposite. Deadheading is the process of cutting off the dead blossoms so that the plant doesn’t make seed pods. This makes the plant focus its energy on growing additional blossoms for the next year instead of making seeds. You need to leave the dead flower heads on the bush if you want seeds.

Why didn’t my lilac bush make any seed pods this year?

There are a number of reasons that could be the case. Your lilac could be a hybrid that doesn’t make seeds that can grow into new plants. It might not have been able to pollinate because the weather was too cold, rainy, or windy when it was in flower. If you only have one lilac shrub and no other lilac bushes around, there may not have been a good partner for cross-pollination.