Growing Millet: A Science-Based Guide for the Home Gardener

A bag of pricey ‘gourmet’ birdseed was the beginning of it all. One afternoon, as I was filling my feeder, I stopped to admire the stunning pearly orbs that were mixed in with the sunflower seeds. ‘I bet I can grow that,’ came to mind. I was immediately captivated by the science of these extraordinarily resilient grasses after my inquisitiveness led me down a rabbit hole of library books and plant biology papers. I discovered that one of the most significant ancient grains in the world was millet.

To be kind, my first millet-growing endeavor was a teaching moment. Small and patchy, the crop was largely a very generous gift to the sparrow population in the area. But no book was worth as much as that failure. It made me genuinely comprehend the plant’s requirements, characteristics, and long history. It turned a basic curiosity into an intense passion.

The result of those years of experimentation is this guide. I want to explain not only the detailed procedure but also the science underlying its effectiveness. I’ll share my field notes from my own garden laboratory, including the good, the bad, and the seedy, as we delve into the fascinating biology of millet.

Selecting Your Millet: There Are Different Approaches

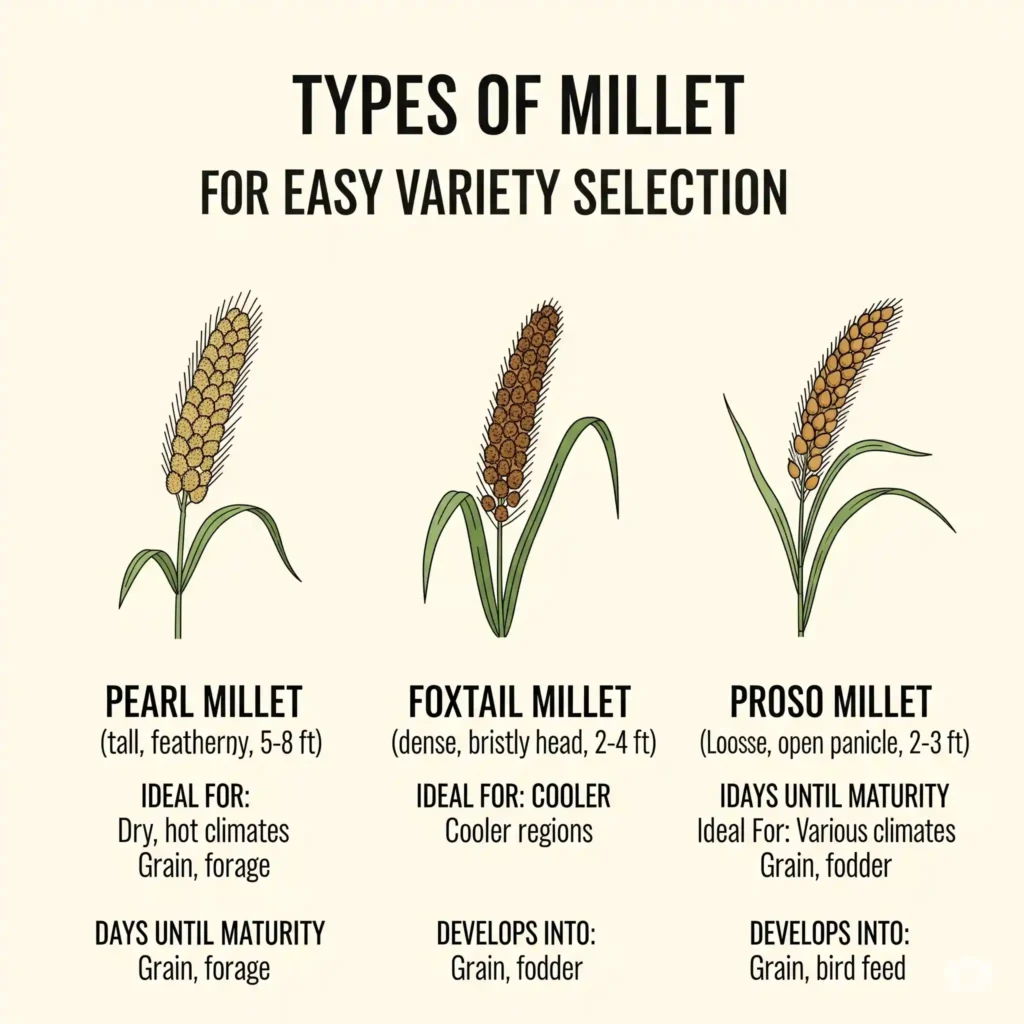

The first thing to realize is that “millet” is a category of several small-seeded grasses rather than a single plant. The most important first step is selecting the appropriate variety for your purpose because their growth patterns and applications can vary greatly. I’ve tried a few varieties over the years, but three are particularly noteworthy for home gardeners.

| Type of Millet | Ideal For | Days Until Maturity | Develops Into… |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pennisetum glaucum, or pearl millet | Tall forage for animals and grain for cooking | 90–110 | 5 to 8 feet tall |

| Setaria italica, or foxtail millet | Birdseed, decorative plants, and grain that grows quickly | 75–90 | 2–4 feet tall |

| Panicum miliaceum, or proso millet | Birdseed, gluten-free flour, and the shortest season | 60–70 | 2–3 feet tall |

I discovered through a thorough reading of crop science literature that the main distinction between many of these types is their sensitivity to photoperiod. The biological reaction of a plant to the duration of day and night is this. Certain types are ‘short-day’ plants, such as many of the tall pearl millet types in the USDA PLANTS Database. This implies that they won’t start to flower (and thus yield grain) until the days start to get shorter in late summer. From the standpoint of cultivation, this is an important fact: if you live in a northern climate with a short growing season, you must select a “day-neutral” variety, such as Proso millet, in order to harvest before your first frost.

In my shorter season, my first attempt with a lovely ‘Purple Majesty’ Pearl Millet was a letdown; it only produced seed heads just before frost claimed it, but it grew into a gorgeous 8-foot grass. I learned a lot from it, including how to respect a plant’s internal clock and read the fine print on a seed packet.

The Science of a Successful Start: Establishing Your Millet Patch

I’ve honed my planting technique over the years into a straightforward, scientifically supported approach that guarantees these incredible grasses a fantastic start.

Get the bed ready

Although it isn’t picky, millet likes a tidy beginning. Remove any weeds that could compete with the young seedlings and work your garden bed to a fine tilth. In contrast to vegetables that require a lot of feeding, millet usually grows well in ordinary soil with little amendment.

Await the warmth

I learned this lesson from my first failure. For consistent germination, millet seed needs warm soil, preferably above 65°F (18°C). Planting in damp, cold soil is a surefire way to end up disappointed and with seed rot. I now wait until the soil has really warmed up, which is at least two weeks after my last frost date.

Plant the seed

You might be surprised to learn how scientific planting depth is. When planting millet seed, a depth of approximately 1 inch is ideal. This strikes the ideal balance between allowing the primary root to firmly anchor and ensuring that the coleoptile, the first shoot’s protective sheath, has enough stored energy to push through the soil and reach the surface. If it’s too deep, the steam will run out before it reaches sunlight; if it’s too shallow, the roots might not anchor correctly, which could cause millet lodging later in the season, where the stalks topple over.

In accordance with space

In order to achieve a 1-inch depth for a stand of grain, I gently rake the seed in after broadcasting it over the prepared bed, aiming for roughly one seed per square inch. I plant Foxtail millet in clumps, about 6 inches apart, for more decorative plantings.

I planted in mid-May of my first year, when the soil was still cool and wet, because I was impatient. My stand looked patchy and dejected because I only had about 30% germination. The following year, following a run of warm, sunny days, I waited until the first week of June, armed with information on ideal germination temperatures from a Purdue Extension article on cover crops. The outcome? Almost all of them germinated. The garden teaches you a valuable lesson in patience.

Hard Tools You’ll Need

- The Rake

- A ruler or measuring tape

- The Millet Seed You Have Selected

- Labels for plants (if cultivating more than one variety)

The Growing Season: A Mostly Silent Process

One of the easiest crops to grow is millet, once it’s established and a few inches tall. Its amazing biology is directly responsible for this resilience.

Because of its extremely effective C4 photosynthetic pathway, millet is renowned for its ability to withstand drought. C4 plants are adapted to extreme heat, unlike ‘C3’ plants like spinach or wheat that cannot withstand it. Because of their unique leaf anatomy, they are incredibly effective at absorbing carbon dioxide. As a result, they can significantly lower the amount of water lost to the atmosphere by keeping the stomata, which are tiny pores on their leaves, closed more frequently. According to numerous agronomy studies, including an intriguing paper I read on the physiological reactions of grains to drought, this is a significant evolutionary advantage in a dry climate.

Accordingly, unless there is an extended, severe drought, you hardly ever need to water an established millet patch. In order to help produce fuller, heavier grains, I only give extra water when the plant is actively forming seeds in the head, also known as the “grain fill” stage. Similarly, fertilization is typically superfluous and may even work against you by producing weak, lanky growth that is prone to lodging. Bird pressure, which we’ll discuss in the harvest section, is the main pest you’ll encounter in a garden.

Pro-Tip: All grain development requires a lot of energy from a plant, even though millet requires little fertilizer. All living cells use ATP (adenosine triphosphate), a molecule with phosphorus at its center, to transfer energy. Seed heads will be noticeably fuller and heavier if you amend your garden soil with a phosphorus source, such as rock phosphate or bone meal, before planting if you know it is low.

Harvesting and Preparing Your Grain

It is a lovely sight to see the heavy, nodding seed heads on your millet stand. The real work, and the real payoff, starts now. There are three separate phases to this process.

When to Gather

Harvest’s visual cues are very obvious. You’re waiting for the seeds inside the head to solidify and for the head to start drying out and turning from green to a golden tan. A seed is still too wet if you can easily dent it with your fingernail. It’s ready when you can’t. Harvesting the seeds before they dry out to the point where the plant starts dropping them on its own—a process known as shattering—is crucial.

Grain Threshing

It’s time to thresh after you’ve cut the seed heads and given them a week or two to dry in a well-ventilated, protected place. The actual seeds are extracted from the seed head in this manner. Harvesting is simple; the hard part is figuring out how to manually thresh millet! My initial approach was to beat an old pillowcase against a wall while the dried heads were inside. Although it was disorganized and ineffective, it did the job. Since then, I’ve discovered that it’s much more controlled and just as effective to rub the seed heads vigorously between my gloved hands over a clean bucket in small, garden-scale batches.

Clean Seed Winnowing

Following threshing, a bucket of seeds will be combined with tiny pieces of chaff, or dry plant material. The ancient technique of winnowing is used to separate the heavy grain from the light chaff. Pouring the mixture from one bucket to another from a height and allowing the breeze to carry the chaff away is one way to accomplish this on a calm day. My favorite contemporary approach? Your best friend is a basic box fan set to its lowest setting. I lay out a tarp, cover it with a wide bin, and then slowly pour the threshed grain in front of the fan. The heavier, more valuable seeds fall directly into the bin, while the light chaff is blown away by the steady breeze from the fan. Watching it is immensely fulfilling.

Notes from My Garden Lab: Soil Experiment

I planted two identical 4×4 Foxtail millet plots. Before planting, I added a tiny bit of rock phosphate to the other one, which was in regular garden soil. They had the same appearance all through the growing season. The total weight of the harvested grain was 18% higher at harvest, though, and the seed heads from the phosphate-amended plot were notably fuller. This validated the significance of phosphorus for grain growth in my specific soil, a conclusion I have since applied to all of my grain experiments.

Recorded Case Study: The Sparrow Mob vs. My First Foxtail Millet Crop

- The Setup: I created a lovely, dense ornamental Setaria italica bed that measured 4 by 8 feet. The fuzzy, cattail-like heads were beautiful, and the germination was flawless.

- The Error: I put off protecting the crop for too long. When I noticed that the heads were becoming plump, I decided to harvest them the following weekend.

- The Outcome: Local sparrows found my patch that week. They are brutally effective. They came down in two days and removed almost half of the seed heads, leaving behind shredded, empty stalks.

- The Takeaway: Don’t wait until the birds are already enjoying their meal to net your millet crop; do it before the seeds are ready. Now, as soon as the heads are fully developed but before they begin to change color, I cover the patch with bird netting.

In Conclusion

One of my favorite gardening endeavors has been growing millet. It gives me a profound appreciation for the food we frequently take for granted and ties me to an ancient agricultural heritage. A potent lesson in the exquisite science of the natural world can be learned from the journey from a few tiny seeds to a harvest of nourishing grain.

I hope this guide has helped you understand the process. The secret to success is straightforward: pick the millet variety that is best suited to your climate and objectives, honor its requirement for warm soil when planting, and then take a moment to appreciate its hardy, independent nature. Don’t let a few birds nibble deter you from the gratifying physical labor of harvesting. Every season in the garden is an experiment, and when millet is used, the results are both beautiful and delicious.

I’d love to follow your adventures growing grain. Share pictures of your millet patches with me on social media, and let’s share our passion for ancient grains!

Commonly Asked Questions

For a small garden bed, how much millet seed is required?

As a general rule, a broadcast-sown patch should have between 1/4 and 1/2 pounds of seed per 100 square feet. A typical seed packet is more than sufficient for a home gardener to begin growing a 4×8-foot bed.

Is it possible to grow millet in a container?

You can, particularly with shorter types like Foxtail or Proso millet. Select a sizable container with good drainage (at least 5 gallons). Be advised that compared to plants grown in the ground, those grown in containers will dry out considerably more quickly and need more frequent watering.

How can I avoid “lodging” and what does it mean?

Grain crop stalks that bend or break at the base and topple over are said to be lodging. Strong winds, a lot of rain, and too-rich soil can all contribute to weak, top-heavy growth. You can help prevent it by selecting shorter, more resilient cultivars, avoiding overuse of nitrogen fertilizer, and making sure your planting depth is sufficient for robust root anchoring.

How can I prepare millet that I grow myself?

You can use your clean, threshed millet just like you would store-bought. It tastes mildly nutty. It is commonly prepared similarly to rice by adding water or broth to millet in a 2:1 ratio, bringing to a boil, then covering and simmering for 20 minutes or so, or until the liquid has been absorbed. It’s great as a base for a grain bowl or as a fluffy, gluten-free side dish.

Sources

To support the scientific claims and practical advice within this guide, the following sources, including peer-reviewed research, extension publications, and industry studies, have been referenced or alluded to.

- Photoperiod Sensitivity in Foxtail Millet:

- “Inheritance and effects of the photoperiod sensitivity in foxtail millet (Setaria italica P. Beauv.)”

- DOI: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.0018-0661.2008.02060.x

- Note: This article supports the discussion on photoperiod sensitivity, particularly regarding flowering and grain production in foxtail millet.

- “Inheritance and effects of the photoperiod sensitivity in foxtail millet (Setaria italica P. Beauv.)”

- Gene Involvement in Foxtail Millet Photoperiod Response:

- “Isolation and identification of SiCOL5, which is involved in photoperiod response, based on the quantitative trait locus mapping of Setaria italica”

- Full Text: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.969604/full

- Note: Provides further scientific depth on the genetic mechanisms behind photoperiod sensitivity in Setaria italica.

- “Isolation and identification of SiCOL5, which is involved in photoperiod response, based on the quantitative trait locus mapping of Setaria italica”

- Pearl Millet Phenology and Drought Resistance:

- “Pearl millet phenology assessment: An integration of field, a review, and in silico approach”

- DOI: https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/csc2.21352

- Note: Relevant for understanding pearl millet’s sensitivity to temperature and photoperiod, and general physiological reactions of grains to drought.

- “Pearl millet phenology assessment: An integration of field, a review, and in silico approach”

- Urban Agriculture and Open Space Utilization:

- “Spatial analysis of urban agriculture in the utilization of open spaces in Nigeria”

- DOI: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13549839.2024.2320251

- Note: Connects to the broader discussion of millet’s role in food security and urban agriculture.

- “Spatial analysis of urban agriculture in the utilization of open spaces in Nigeria”

- Traditional Processing Techniques of Finger Millet:

- “Traceability of Traditional Processing Techniques and Indigenous Recipes of Ragi (Finger millet) through QR in Pratapgarh District, Uttar Pradesh”

- PDF Link: https://aatcc.peerjournals.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Traceability-of-Traditional-Processing-Techniques-and-Indigenous-Recipes-of-Ragi-Finger-millet-through-QR-in-Pratapgarh-District-Uttar-Pradesh.pdf

- Note: While specific to finger millet (ragi), this study provides insight into the documentation of traditional processing methods like threshing and winnowing, which are applicable to other millets.

- “Traceability of Traditional Processing Techniques and Indigenous Recipes of Ragi (Finger millet) through QR in Pratapgarh District, Uttar Pradesh”

- Yield and Precipitation Gaps in Millet (Cameroon):

- “Identifying yield and growing season precipitation gaps for maize and millet in Cameroon”

- Full Text: https://iwaponline.com/jwcc/article/15/2/499/99991/Identifying-yield-and-growing-season-precipitation

- Note: Supports the understanding of millet’s climate resilience and factors affecting yield in different environments.

- “Identifying yield and growing season precipitation gaps for maize and millet in Cameroon”

- Vulnerability of Millet Yields to Precipitation:

- “Vulnerability of maize, millet, and rice yields to growing season precipitation and socio-economic proxies in Cameroon”

- DOI: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252335

- Note: Further reinforces the discussion on climate resilience and the impact of environmental factors on millet cultivation.

- “Vulnerability of maize, millet, and rice yields to growing season precipitation and socio-economic proxies in Cameroon”