The Complete Guide to Growing Celery in Pots for a Perfect Harvest

TL;DR

- Celery isn’t difficult, it’s honest: Success with celery comes from understanding and consistently meeting its high demands for water and nutrients. It’s not for the forgetful gardener.

- Choose the right variety for pots: For beginners, cutting/leaf celery (e.g., ‘Amsterdam Seasoning’) is recommended. It’s grown as a “cut-and-come-again” herb, is more forgiving, and provides a steady harvest of flavorful leaves and thin stalks. Stalk celery (e.g., ‘Utah Tall’) is a more challenging project.

- Understand its needs: Celery has a shallow, fibrous root system and is over 95% water, making it extremely thirsty. Consistent moisture is more important than heavy watering; a cycle of drying out and soaking will create tough, bitter stalks.

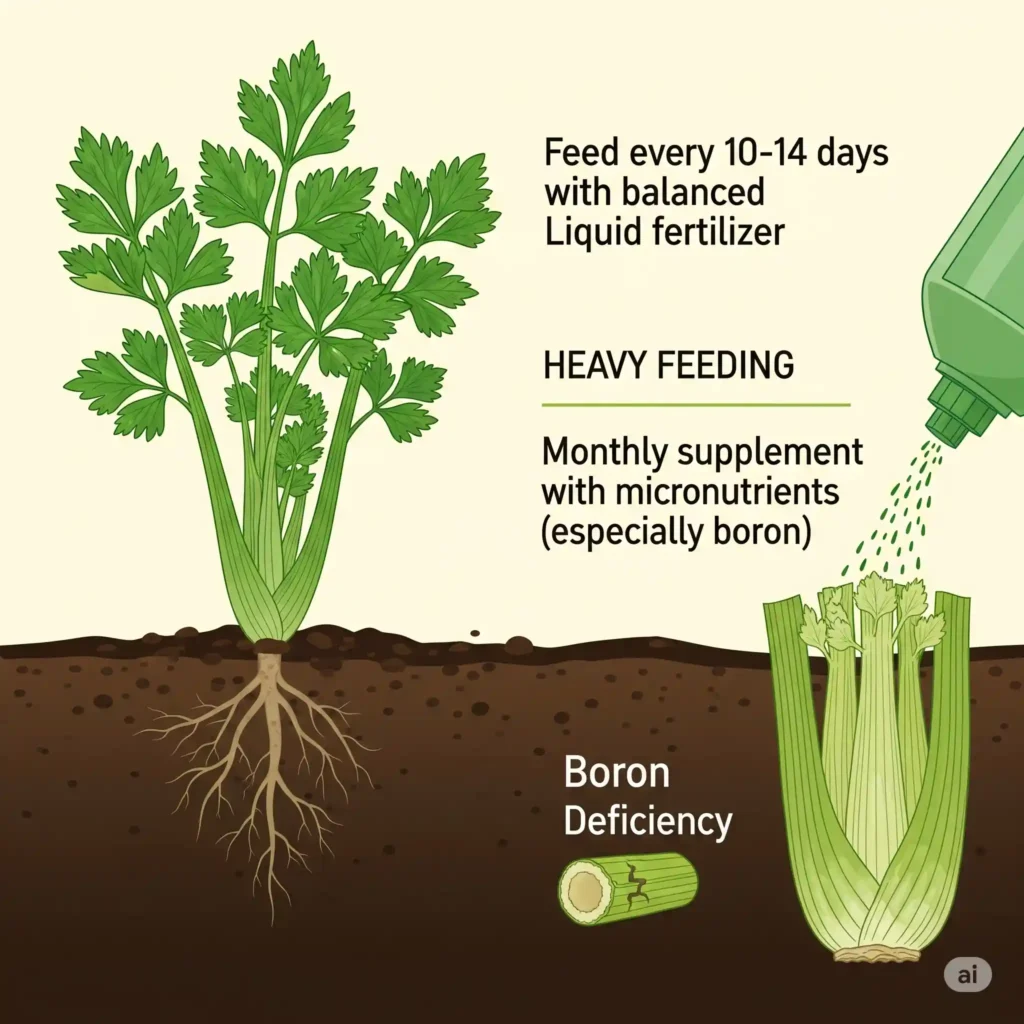

- Feed it heavily: Celery is a “luxury consumer” of nutrients. Feed every 10-14 days with a balanced liquid fertilizer, and supplement monthly with a fertilizer containing micronutrients, especially boron, to prevent hollow, cracked stalks.

- Use the right container and soil: A self-watering container is the ideal choice. Use a rich, water-retentive soil mix of 60% potting mix, 30% compost, and 10% perlite.

- Blanch for best flavor: For stalk celery, blanching (blocking light from the stalks) 2-3 weeks before harvest is crucial for developing a tender, sweet, and less bitter flavor.

The Unforgiving Truth About Celery

In the gardening world, celery has a bad reputation that even experienced gardeners are afraid of. People say it’s picky, demanding, and very hard to cultivate. For people who plant in small spaces, the concept of growing this cool-weather crop on a patio or balcony can seem unattainable. It’s a task better left to people with big, well-maintained garden plots. But what if I told you that celery is hard to grow not because it’s complicated, but because people don’t understand what it needs?

Celery isn’t hard; it’s just truthful. It is one of the most talkative plants in the yard. It will tell you exactly what it needs, and it won’t forgive you if you don’t give it to it. If you don’t pay attention to something for only one afternoon on a hot day, it could have implications. There are no hidden, complicated ways to succeed. The key is to have a profound and respected understanding of how this plant works. This handbook is meant to be the most complete reference for people who cultivate in containers. We will go beyond simple planting instructions to explain the science behind celery’s acute thirst and hunger, show you kinds that are perfect for container life, and break down advanced techniques like blanching that may turn your yield from good to gourmet. Forget what others say; if you know what you’re doing, you can definitely have a crisp, tasty, and plentiful harvest from a pot.

Choosing the Right Celery for Your Pot Is the Most Important Thing

The sort of celery you cultivate is the most important thing that will determine how happy and successful you are as a container gardener. Your pick will affect the style of your harvest, the time frame, the strength of the flavor, and how hard the endeavor is altogether. Before you ever buy a seed or a pot, this choice sets the stage for everything that will happen.

The Real Deal on Growing Celery from Scraps

First, let’s talk about the most common online hack. It’s a fun and interesting kitchen science project to grow a new celery base from one you bought at the shop. It’s also a great method to teach kids about plants. You put the base in a shallow dish of water, and in a few days, new, bright green leaves start to grow from the center. It seems like magic. But it’s important to know how the body works and to have realistic expectations. The celery base is using the energy it has stored in its tissues to push out leaves. It is not producing new roots that can support the growth of thick, crisp stalks.

You will get a nice crop of celery leaves that smell and taste great, as well as a few very thin, reed-like stalks. This is great for giving soups, stocks, salads, and stir-fries a strong, fresh celery flavor. You won’t get a new head of thick, crunchy, full-sized celery stalks. To do that, you need to grow a whole plant from seed or transplant it. This plant will have the genetic code and strong root system it needs to develop so quickly.

Stalk Celery, like “Utah Tall”

This is the kind of celery you see in stores all the time. It’s grown just for its thick, crispy, water-filled petioles, which are the stalks. The hardest way to grow a good head of stalk celery is also one of the most rewarding. To get the finest flavor and texture, it needs a lengthy, cold growth season (usually 100–120 days after transplant), a steady and heavy supply of water and nutrients, and sometimes blanching helps. People appreciate the ‘Utah Tall 52-70R’ kind since it is strong and doesn’t get sick as easily as other types. This is a project for serious gardeners who want to grow a classic crop in a place that isn’t usually used for growing crops.

Cutting Celery or Leaf Celery (The Container Gardener’s Secret Weapon)

This is the less prevalent option, but I think it’s the better one for container gardening. People plant types like “Amsterdam Seasoning” or “Par-Cel” not for one big head, but for a steady supply of leaves and thin stalks. It grows in a “cut-and-come-again” way, which means you can pick the outer stalks and leaves as you need them, while the plant keeps making new growth from the center. The taste is usually stronger and more fragrant than stalk celery, which makes it a great ingredient for cooking. It tastes better, needs less water and nutrients, and is far more forgiving of the inevitable problems that come up in a container environment. This makes it a great place to start.

Expert Tip

If you’re new to growing celery in a pot, I strongly suggest starting with a cutting celery type. The payoff is quicker, more consistent, and far more dependable. It provides you all the celery flavor you need for cooking, and it’s far easier than cultivating a perfect head of stalk celery. This will help you feel more confident in the future.

Why Celery Is So Thirsty and Hungry: The Science Behind It

To take care of celery in a container, you need to know how its body works. The way it is built and what it is made of makes it “demanding.” It’s not trying to be hard; it’s just following its biological needs.

The Fibrous, Shallow Root System

Celery has a shallow, fibrous root system that makes a thick, thirsty mat just a few inches below the soil surface. This is different from a tomato, which has a taproot that goes deep into the ground. This anatomical feature is the main reason why it can’t stand drought very well. The sun and wind dry up the top few inches of soil in a container initially. This unstable zone is where celery’s entire root system dwells, thus even a short time of dry soil can produce stress right away, which can damage cells and make the stalks rough and stringy.

The Needs of Stalks Full of Water

Over 95% of a crunchy celery stalk is water. The plant has to constantly pull water from the soil and circulate it through its structure to make these juicy, water-filled tissues. This is called transpiration. This process works like a biological pump, moving water from the roots up through the stalks to the leaves, where it evaporates. Because of this and its shallow roots, it has to stay moist all the time. If you let the plant become thirsty enough to droop before watering it, it will go through a cycle of wilting and reviving. This will make the stalks tough, stringy, and bitter because the plant makes more fibrous lignin to deal with the stress.

Nutrients Needed for Fast Growth

People often call celery a “luxury consumer” of nutrients since it eats a lot. It needs a stable, constant supply of important nutrients to create its cells and keep its metabolism going since it grows so quickly.

- Nitrogen (N): This is what makes all the green, leafy plants grow. To make big, robust leaves, the plant needs a consistent supply of water. These leaves then work as solar panels to make electricity for the rest of the plant.

- Potassium (K): This element is very important for controlling the water pressure (turgor) inside plant cells. It directly affects the strength, crispness, and stress resistance of the stalks.

- Boron (B): This is the most important micronutrient for celery. Boron is necessary for cells to take in calcium and for making cell walls that are robust and flexible. The most typical problem with plants is that their stalks split, turn brown, and become hollow. This is because they don’t have enough boron, which may easily happen in a container where nutrients are limited and can be leached away.

- Calcium (Ca) and Magnesium (Mg): Calcium is another important part of cell walls, and Magnesium is the main atom in every chlorophyll molecule. Lack of nutrients can cause leaves to turn pale and yellow and growth to slow down.

Things People Often Get Wrong

- Myth: “Celery only needs a lot of water.”

- Truth: It needs a steady supply of water. It is worse to have a cycle of dry and wet than to maintain it a little less wet but steady. This cycle makes stalks that are tough and stringy.

- Myth: “Any balanced fertilizer will do.”

- Truth: A balanced fertilizer is a fine place to start, but it might not include enough boron and other trace minerals. If a plant has hollow or fractured stems, it needs a fertilizer that has trace micronutrients in it.

- Myth: “Celery likes wet, swampy places.”

- Truth: Celery likes wet soil, but it hates soil that is too wet and doesn’t drain. It needs oxygen to live because its roots are fibrous. If you grow celery in a pot that doesn’t drain well, the roots will rot, which is a deadly ailment.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Planting Celery in Pots

A healthy plant starts with the right way to plant it, whether you start with seeds or transplants. This is where you put what you know about the plant’s demands into action.

Soil and Container

A self-watering container is the best choice for celery because it has a built-in reservoir that keeps the soil moist all the time, which keeps the plant from being stressed out when it dries out. If you’re using a regular pot, make sure it’s at least 8 inches deep and 8 to 10 inches broad for each plant. You need to make a special soil mix for it because it needs a lot of food and water.

The best recipe for container celery soil is:

- 60% High-Quality Potting Mix: This is what holds everything together. Pick a mix that has a lot of organic materials and is made to not get compacted over a lengthy season.

- 30% High-Quality Compost: This is the mix’s main ingredient. It has a lot of organic content that helps hold water, a slow-release source of many nutrients, and a lot of helpful bacteria.

- 10% Perlite: This keeps the mix from getting too dense and lets the roots breathe. Good drainage is very important in a circumstance like this where there is a lot of water to keep the roots from rotting.

Beginning with Seed

Celery seeds are quite small and take a long time to sprout. You need to start them inside 10 to 12 weeks before the latest frost date.

- Put a sterile, fine-textured seed-starting mix in a seed tray.

- To sprout, celery seeds need light. So, plant them right on top of the mix. Do not put dirt on top of them. To make sure they touch well, press them down gently.

- Use a spray bottle to mist the surface well so that the small seeds don’t move. Put a plastic humidity dome over the tray to keep the moisture level steady.

- Put the tray in a warm place, such 70–75°F (21–24°C). A heat mat can help seeds sprout much faster. Be patient; it could take three weeks.

- Take off the dome after the seedlings come up and put them under powerful grow lights to stop them from being weak and lanky.

Putting in Transplants

It’s time to put your seedlings in their final pot once they have a few sets of true leaves and the risk of frost has passed. First, you need to “harden them off.” This is the most important step in getting your delicate indoor seedlings used to the harsh circumstances outside, such sun, wind, and changing temperatures.

- Day 1-2: For 1 to 2 hours, put them in a shaded, safe place.

- Day 3–4: Put them in the morning sun for two to three hours.

- Days 5 and 6: Let them spend more time outside and get more direct sunlight.

- Day 7: Keep them outside all day.

Put the transplant in the pot at the same depth as it was in its nursery cell when you plant it. Don’t bury the crown, which is the main growing point, because this can make it decay.

Don’t worry if your celery seeds don’t sprout for up to three weeks. They are known for being sluggish. I usually plant more than I think I’ll need. Soaking the seeds in warm water overnight before planting might sometimes assist to make the seed coat softer and speed up the process.

How to Blanch Celery in a Pot

Blanching is the old-fashioned way to make celery stalks softer, sweeter, and less harsh. It’s easy to modify for containers. It is a simple method that gives amazing results, making your fresh celery taste like it came from a fancy restaurant.

The Science of Blanching

Blanching is only the act of blocking light from the growing stalks. When a plant gets sunlight, it makes green chlorophyll. You stop chlorophyll formation by blocking the light. This makes the stalks pale and soft, with a gentler, less harsh taste. The lack of light also stops the growth of some phenolic chemicals that taste bitter and makes cell structures that are less fibrous and more juicy. It doesn’t have to be used to cut celery, but it makes regular stalk celery taste a lot better.

When to Begin

Start the blanching process when the stalks are 8 to 10 inches long and growing quickly. This is usually two to three weeks before you want to start your big harvest. You want the plant to have enough leaves to keep photosynthesizing and growing while the stalks are covered.

Ways to Blanch in a Container

- The Cardboard Collar: This is the simplest way. Wrap a piece of corrugated cardboard (like a piece from a shipping box) around the base of the plant to make a tube or collar. Tie it down with string. The cardboard keeps the light out, but the leaves at the top can still get sun.

- The Wax Carton Method: To use the Wax Carton Method, cut the top and bottom off of a half-gallon milk or juice carton. Carefully bring the celery stalks together and slide the box over the young plant, pushing it down into the ground a little. This makes a strong, waterproof collar.

- Hilling Up: You can gently mound loose, light materials like straw, shredded leaves, or even extra potting soil around the base of the plant in a big, deep container. Don’t let soil get into the middle of the crown, because this can hold moisture and make it decay.

When you put on the blanching collar, ensure sure the top foliage growth is completely exposed to the sun. The leaves are like solar panels for the plant. They need to keep photosynthesizing to make the stalk grow. You are merely trying to cover the stalks.

Long-Term Care and Harvesting

Proper harvesting keeps the plants growing, and a regular care regimen is the key to a long and productive season.

How to Harvest

Pulling the stalks off the plant might hurt the delicate crown and mess with the thin root system. Always pick the outermost, most mature stalks first if you want to keep getting crops. Cut the stalk at its base with a clean, sharp knife. This lets the younger, inner stalks keep growing. You can start picking individual stalks as soon as they are big enough to utilize. You can either pick individual stalks of celery as you need them or wait until the whole head has grown to the right size and pick the whole plant at once.

A Schedule for Feeding in Detail

You need to be careful and consistent if you want to grow celery in a container that has a lot of nutrients.

- Every 10 to 14 days, without fail, give them a balanced, water-soluble fertilizer. You should think of it as part of your normal watering schedule.

- To avoid nutrient deficits, replace this with a liquid fertilizer that has a full spectrum of micronutrients, including boron, once a month. This is a great organic option because it is full of trace minerals.

Guide to Fixing Problems

Stalks that are cracked and hollow

Reason: Not enough boron. This is a classic sign of this micronutrient shortage, which happens when there isn’t enough boron for cells to build their walls. Answer: Feed right away with a fertilizer that has boron in it, like liquid seaweed. Make sure that your monthly feeding includes all of the micronutrients.

Bolting (Sending Up a Flower Stalk)

Reason: Stress from the temperature. The plant thinks winter is over and now is the time to reproduce. This happens a lot when young transplants are suddenly exposed to cold weather in the spring (temperatures below 55°F / 13°C for a long time). Answer: You can’t stop a plant from bolting once it has started. Pick the whole plant right away. The stalks will still be safe to eat, but they will get harsher and more bitter quickly as the plant uses its energy to make flowers.

Stalks that are tough and stringy

Reason: Watering that isn’t always the same. When a plant goes through a dry spell and then is watered, it makes tough, fibrous fibers (lignin) as a way to deal with stress. Answer: Make sure the moisture level stays the same. The best answer is a container that waters itself. Don’t let the pot get fully dry. Covering the top of the soil with mulch can also help keep moisture in.

Miner of Celery Leaves

Reason: Bug. There will be tell-tale white, squiggly lines inside the leaves where the tiny larva is tunneling and eating the leaf tissue between the top and bottom surfaces. Answer: This pest is mostly a problem with looks. Take off and throw away any leaves that are impacted right away to stop the larva from growing up and having babies. This is usually all you need to do to keep things under control in a home garden.

Snails and slugs

Reason: Bug. Look for holes that aren’t even in the stalks and leaves. These holes are often followed by slimy trails. Answer: Pick pests by hand at night. You can use iron phosphate slug baits, which are harmless for pets and wildlife, or you can make barriers around the pot’s edge using crushed eggshells or copper tape.

Final Thoughts

People say celery is hard to grow, but that’s not true. This plant isn’t for a careless gardener, yet it rewards hard work and understanding. Any container gardener may have a tasty and satisfying crop by understanding their plant’s unique and honest requirement for consistent moisture and nutrients, picking a variety that fits their aims, and employing basic but efficient methods like blanching. Homegrown celery has a crisp, strong smell and taste that is worth working for. With the information you have now, you can definitely get it.

Questions and Answers

Can I plant celery in a pot inside?

It’s really hard. Celery needs a lot of direct sunshine (6–8 hours or more) to develop well, which is almost impossible to do indoors without strong, dedicated grow lights. It grows best outside.

Why does my celery have a bitter taste?

Two things that usually make things bitter are not enough water and too much heat. Watering the plant at different times might stress it out, and hot summer weather can make the flavor stronger and more bitter. The best method to deal with this is to blanch.

How many celery plants can I fit in one pot?

To make sure your traditional stalk celery has enough resources to grow a big head, simply plant one per pot that is 8 to 10 inches in diameter. You can plant two or three celery plants in the same container because you will be cutting the outer leaves and stalks all the time.

What sets celery apart from celeriac?

They are all types of the same plant, Apium graveolens. People grow celery for its stalks and leaves. People grow celeriac (or celery root) for its big, bulbous root. The stalks are usually harsh and not eaten.

Is it true that celery has “negative calories”?

A lot of people believe this myth. Celery has extremely few calories (around 10 per large stalk), yet your body doesn’t spend more calories digesting it than it has. The thermic effect of food is the process of digestion. It utilizes a little bit of energy, but not enough to lose more calories than you eat.

Is it okay to use the same soil again when my celery is done?

At the conclusion of the season, the soil will be very low in nutrients because celery needs a lot of them. You shouldn’t plant another heavy feeder in the same soil. You can, however, add a lot of new compost and a balanced granular fertilizer to the old soil before using it for a light feeder like lettuce or herbs.