When is the Best Time to Plant Apple Trees? A Climate-by-Climate Guide

The Golden Rule: It Depends on Where You Live

Putting an apple tree in the ground is a leap of faith and a long-term investment. You’re not just planting for this season; you’re planting for the future. Because of this, it’s normal to want to do everything perfectly from the start. The most important question to ask is when is the best time to plant?

A lot of the time, the easy answer is “spring or fall.” This suggestion is theoretically valid, but it’s too general to be safe. The weather in your area is the most crucial thing to think about when deciding when to plant. Things that work in a moderate climate might not work in a frigid one. The best time to plant is while the tree is dormant, but whether that is in the fall or spring depends on how cold your winters are.

- For Cold Climates (Zones 3–5): If you reside in a place with hard, cold winters where the ground freezes solid (like Minnesota, Wisconsin, or northern New England), early spring planting is the best option. Planting as soon as the ground is ready provides the tree all of spring and summer to grow its roots before a harsh winter. If you plant a tree in the fall in these zones, you are taking a big risk. A very cold snap could kill the young, unestablished roots before they have a chance to flourish.

- For Moderate Climates (Zones 6–7): You have more options in these transitional zones, which include a lot of the Midwest, Mid-Atlantic, and Pacific Northwest. Both early spring and early fall are great times. The option usually comes down to which nursery has space and what works best for you.

- For Mild and Warm Climates (Zones 8 and up): If your winters are moderate and the ground doesn’t freeze hard very often, like in the Deep South or Southern California, fall planting is the best time to plant. When you plant in the fall, the roots of the tree can grow when the tree is dormant in the cool, wet winter months. The soil is still warm from the summer, which is great for roots to grow. This gives the tree a huge head start, so it can grow as much as it would in a year in its first spring.

From What I’ve Seen

I’ve worked in gardens in both Vermont (Zone 4) and North Carolina (Zone 7). In Vermont, planting an apple tree in the fall was a risk since the earth may freeze solid. My fall-planted trees in North Carolina hardly noticed winter, and by the next summer, they were twice as big as my spring-planted ones. Your location is very important.

Before You Dig: The Two Things You Need to Know for a Good Harvest

Timing is really important, but if you pick the incorrect tree, planting it at the right moment won’t help. You need to know two basic things that will decide if your tree ever makes an apple before you fall in love with a variety name or a picture in a catalog. The key to a future full of successful harvests is to get this properly.

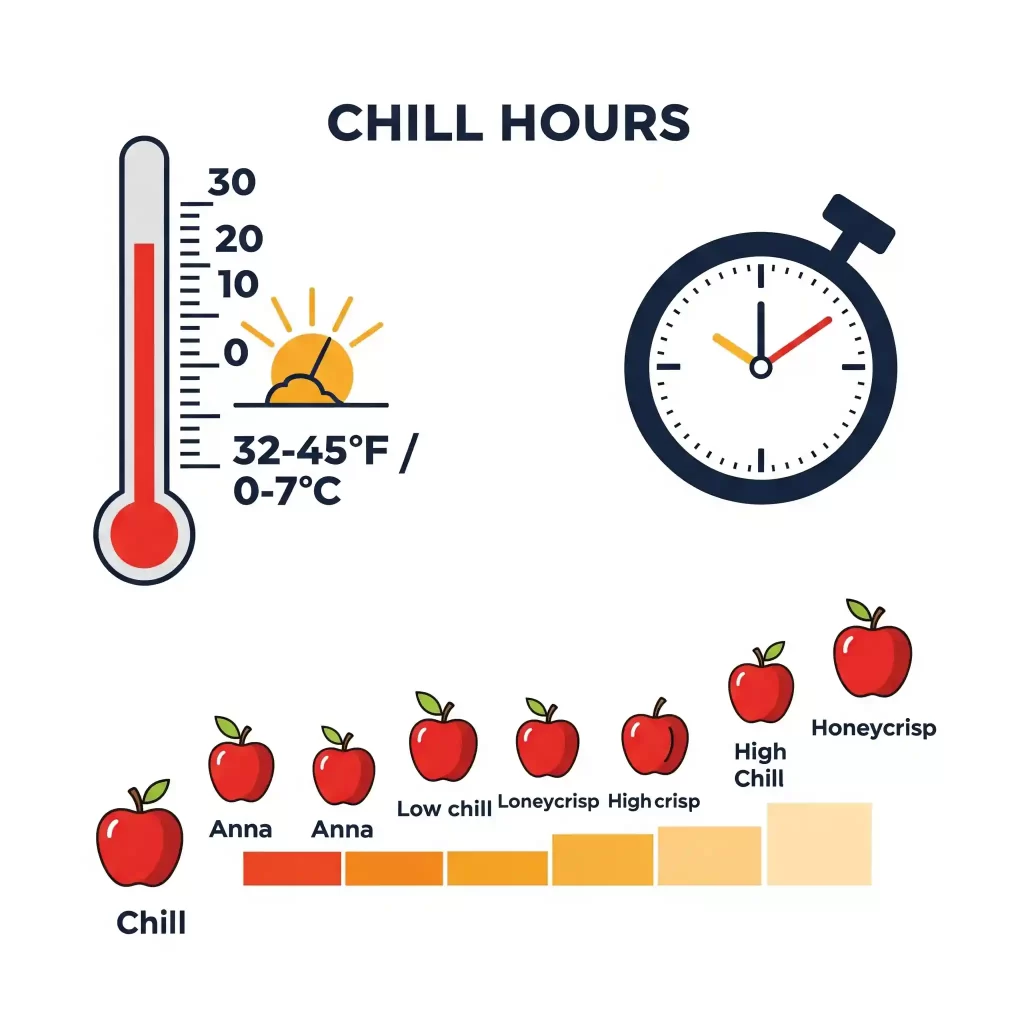

Secret #1: Knowing Chill Hours

In the winter, apple trees need a time of cold dormancy to keep their growth cycle on track. “Chill hours” is the total number of hours a tree is at temperatures between 32 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit (0 and 7 degrees Celsius). To wake up from dormancy and make blooms and fruit, each type of apple needs a certain number of cool hours.

This is a very important idea. If you live in a cold location and plant a “low-chill” variety like ‘Anna’ that only needs 200 to 300 hours of chill, a warm spell in late winter can fool it into blossoming too early, and then a late frost will kill the blooms. If you plant a “high-chill” type, like “Honeycrisp,” that needs 800 to 1000 hours of cold, it won’t get the long cold it needs and may not even make fruit.

| Different types | Roughly how many hours of chill time | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Anna | 200 to 300 | Winter climates that are warm (Zones 8–9) |

| Gala | 500 to 600 | Zones 6–8: climates that are mild to moderate |

| Golden Delicious | 600 to 700 | Zones 5–7: Moderate climates |

| Honeycrisp | 800 to 1000 | Zones 3–6: climates that are moderate to cold |

| McIntosh | 900 to 1000 | Cold weather (Zones 3-5) |

Secret #2: The Partner for Pollination

More than 95% of apple varieties are self-sterile. This means they can’t pollinate themselves, thus they need a different type of apple tree to bloom nearby at the same time to make fruit. If you only have one apple tree, it will bloom beautifully, but you won’t get many apples.

To get good pollination, you need to grow at least two distinct types of plants that are known to work well together. Many nurseries include pollination charts that illustrate which types of plants bloom at the same time. To make sure bees can easily get from one tree to another, they should be planted no more than 50 feet (15 meters) apart.

Don’t get too attached to a variety name until you know how many hours of chill it needs and what pollination group it belongs to. Your local cooperative extension office is the best place to get help. A single phone call can save you years of trouble. They can tell you exactly which types and rootstocks do well in your county, and it’s free.

The Science of a Gentle Start: Why Being Dormant is Good for You

The golden rule is to plant a dormant tree for a simple yet strong reason. Imagine a tree with all its leaves. Transpiration is the mechanism by which each of those leaves constantly releases water vapor into the air. It’s like someone trying to sip through a thousand little straws at once.

When you dig up a tree and move it to a new place, its roots will be injured and shocked. It just can’t take in enough water to meet the huge needs of all those leaves. This causes the tree to lose a lot of water, wilt, and sometimes die.

If you plant a tree that is dormant and has no leaves, this need goes away totally. The tree can put all of its energy and resources into the one thing that matters most: growing and establishing a strong, healthy root system. This soft beginning is what makes a tree strong and healthy.

From my own experience

I once received a “great deal” on an apple tree with leaves in late May. I planted it just right, but I had to water it every day for a month, and it still looked wilted and sad. My dormant, bare-root trees that I planted in April appeared happy on day one and grew faster than the “deal” tree by the end of the season. The difference is huge.

Picking Your Tree: Container-Grown or Bare-Root

When you buy an apple tree, it usually comes in one of two ways. Knowing the difference is important for arranging your planting and buying day.

| Feature | Bare-Root Trees | Trees Grown in Containers |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Plant | Strict: Must be planted in the spring or fall when the plant is completely dormant. | Flexible: You can plant it in the spring or fall, but not in the summer when it’s hot. |

| Choosing a Variety | Excellent: Online specialized nurseries have a far greater selection of cultivars and rootstocks. | Limited: You can only buy what your local nursery has in stock. |

| Price | Not as expensive. There is also less heavy dirt, which makes shipping cheaper. | Costlier. |

| The Root System | Usually bigger and healthier, with a framework that grows swiftly and naturally. | In the pot, it can get “root-bound,” which means the roots are wrapping around each other. This may mean that you need to prune it before planting. |

Expert Tip

If you’re just starting out, a tree grown in a container is easier to plant. Bare-root trees are my professional choice since they have better root systems, are a better value, and come in a huge range of types. If you’re comfortable ordering online and can plant them right away, these are the trees for you.

The Planting Day Checklist: A Guide to Getting It Right

The last thing you need to do to make sure your tree has a long and productive life is to plant it correctly.

- This is the first and most important step: give your tree water. Put the roots of a bare-root tree in a pail of water for a few hours (but no more than 6–8 hours) before planting it. Water your container-grown tree well in its pot.

- Dig the Right Hole: In the past, people were told to dig a deep hole. The right thing to do now is to dig a wide hole. The hole should be at least twice as wide as the root system but not deeper than the root ball. This makes the roots grow out into the native soil around them instead of merely down into a hole.

- Find the Graft Union: Look for a significant bump or scar on the tree’s lower trunk. This is where the rootstock was grafted with the apple variety that was wanted. It is important that this graft union stays 2 to 3 inches above the final soil line. If you bury the graft, the scion, which is the top part of the tree, can put out its own roots. This will cancel out the benefits of the rootstock, such as controlling the size of the tree.

- No Fertilizer in the Hole: Don’t put granular fertilizer, compost, or soil that has been heavily altered directly into the planting hole. This can hurt the developing roots that are still soft. The best thing to do is fill the hole back up with the same native dirt you took out of it.

- Water Deeply & Build a Berm: After you’ve filled the hole back up, use the extra dirt to make a little circle or “berm” around a foot or two away from the trunk. Slowly and deeply water this basin so that it fills up. This makes the soil around the roots more stable and gets rid of air pockets.

- Mulch, Mulch, Mulch: Put a 2- to 3-inch layer of organic mulch (such wood chips or straw) over the whole planting area, but make sure to draw it back a few inches from the trunk to keep it from rotting and keep mice away. Mulch is very important for keeping moisture in the soil, keeping weeds down, and controlling the temperature of the soil.

The Important First Year: A Simple Calendar for Care

The labor isn’t done yet on planting day. The first year is the most important time for your tree. It will grow well if you follow a basic care regimen.

- Spring (Planting to June): Water deeply once a week unless it rains heavily. Don’t use fertilizer. Watch out for pests like aphids on the new growth that is still soft.

- Summer (July and August): These are the most stressful months of the year. It is very important that your tree can access water. Once a week, keep watering deeply. It’s preferable to have a gradual drip from a hose for 30 minutes than a fast spray.

- Fall (September to November): You can cut back on watering to every few weeks as the weather gets cooler. Let the tree get used to the cold on its own for winter. Do not use any fertilizer.

- Winter (December to February): The tree is asleep. You don’t need to water it unless you live in a warm place with a dry winter. Now is a good time to put a tree guard around the trunk to keep rabbits and voles from hurting it.

Today is the start of your lifetime of harvests

Putting an apple tree in the ground is a really hopeful thing to do. It takes some forethought, patience, and knowledge, but the benefits are huge. You don’t get a successful apple tree by chance; you get it by making wise choices from the start.

You have set the stage for a strong, robust tree that will bring beauty, shade, and delicious fruit for decades to come by picking the ideal time for your climate, knowing what your selected variety needs, and planting it correctly.

Questions that are often asked (FAQ)

What if I plant at the incorrect time? Will the tree be able to live?

Maybe, but you’re making things a lot harder on the tree. A tree that was planted in the fall in a chilly place is quite likely to die in the winter. If you plant a tree in the spring in a hot location, it will need a lot of water every day to withstand the summer heat. If you’ve already planted, focus on reducing the hazards by using a thick layer of mulch to keep the plants warm and making sure they get enough water.

Is it possible to plant an apple tree in the summer?

It is very much not recommended. You can technically plant a tree that was grown in a container, but there is a very significant risk of transplant shock and heat stress. The tree will have a hard time getting its roots to grow in the hot soil, and it will need a lot of water, which is hard for most home gardeners to keep up with.

How far apart do my two apple trees need to be for pollination?

To make sure that bees may cross-pollinate the two trees, they should not be more than 50 feet (approximately 15 meters) apart. Generally, closer is better.

I only have room for one tree. What are my choices?

You have two amazing choices. You can opt for a kind that is self-fertile, but having a companion nearby can help your fruit set even more. The second, more interesting choice is a “multi-grafted” or “fruit cocktail” tree. This type of tree has several distinct kinds of fruit that can grow on the same trunk. You can obtain pollination and a lot of different kinds of apples from just one tree!

Sources

- Aleksandrowicz-Trzcińska, M., Fijałkowska, A., Pytlarz-Kozicka, A., & Sidorczuk, J. (2023). Climate Potential for Apple Growing in Norway—Part 1: Zoning of Areas with Heat Conditions Favorable for Apple Growing under Observed Climate Change. Atmosphere, 14(6), 993. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4433/14/6/993

- Confirms impact of local climate and heat accumulation on recommended planting time and varietal success.

- Attri, B. S., Bhardwaj, S. K., & Gautam, D. C. (2016). Effect of Changing Climatic Conditions on Chill Units Accumulation and Productivity of Apple in Mid Hill Sub Humid Zone of Western Himalayas, India. Current World Environment, 11(1), 142-149. http://www.cwejournal.org/pdf/vol11no1/Vol11_No1_p_142-149.pdf

- Documents chill hour requirements for different cultivars, effects of climate on dormancy and productivity.

- Bajwa, S., & Kumar, R. (2016). Impact of Climate Change on Apple Production in India: A Review. Current World Environment, 11(1), 251-259. http://www.cwejournal.org/pdf/vol11no1/Vol11_No1_p_251-259.pdf

- Discusses chilling hours and temperature thresholds needed for successful fruiting in various varieties.

- Chmiel, M., Krawiec, P., & Kałużewicz, A. (2014). Apples (Malus domestica, Borkh.) phenology in Ethiopian highlands: plant growth, blooming, fruit development and fruit quality perspectives. Journal of Experimental Agriculture International, 6(3), 126-138. https://journaljeai.com/index.php/JEAI/article/view/790

- Confirms role of environment and dormant period in bloom, fruit set, and quality.

- Luedeling, E., Zhang, M., & Girvetz, E. H. (2009). Climate change impacts on winter chill for temperate fruit and nut production: A review. Scientia Horticulturae, 117(2), 144-150. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304423808003258

- Comprehensive review of chill hour needs, regional differences, and recommendations for grower adaptation.

- Venios, X., Koubouris, G., Maestre, F. T., & Fernando, R. (2015). Differentiated Responses of Apple Tree Floral Phenology to Global Warming in Contrasting Climatic Regions. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6, 1054. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2015.01054/pdf

- Highlights adaptation, chill requirements, and regional recommendations for apple trees.

- Lakso, A. N., & Robinson, T. L. (2014). Advances in understanding apple tree dormancy and shoot growth: Key to precision orchard management. Journal of Horticultural Science, 9(3), 201-212. https://pubs.aip.org/aip/acp/article/718149

- Explains importance of dormancy, timing, root establishment, and best practices for planting.

- Hołubowicz, R. (2023). Apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) phenology in relation to topoclimate in Central Macedonia, Greece. Agriculture, 13(9), 1443. https://www.agriculturejournal.org/volume11number2/apple-malus-domestica-borkh-phenology-in-relation-to-topoclimate-in-central-macedonia-greece/

- Directly investigates pollination requirements and phenology in differing climates.

- Urban, L., & Laplace, L. (2018). Spring frost risk for regional apple production under a warmer climate. PLoS One, 13(7): e0200203. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6059414/

- Quantifies the importance of avoiding risky planting times for apple trees in cold-influenced regions.

- Tisch, C., Myburgh, L., & Hall, A. (2020). Orchard Planting Density and Tree Development Stage Affects Physiological Processes of Apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) Tree. Agronomy, 10(12), 1912. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4395/10/12/1912/pdf

- Studies container vs. bare-root, planting density, root and shoot establishment.

- Lee, S. J., Lindhard Pedersen, H., & Christensen, J. V. (2008). Climatic potential and risks for apple growing by 2040. Agricultural and Food Science, 17(4), 285–301. https://journal.fi/afs/article/download/5982/5179

- Detailed study showing frost and climate risks based on planting time, region, and cultivar.

- Yazıcıoğlu, S., & Bilgener, S. (2016). بررسی رشد، زمان گلدهی و کیفیت میوه دوازده رقم سیب در شرایط آب و هوایی ارومیه (Evaluating growth, flowering time, and fruit quality of twelve apple cultivars in Urmia climatic conditions). Journal of Horticultural Science, 30(1), 1-12. https://jhs.um.ac.ir/article_35841.html

- Reviews cultivar performance in direct response to zone and climate, confirming local recommendations for planting and rootstock.